February 2, 2015

By Andrias Parmour – Research Assistant

From a political perspective, Christmas extended to beyond the New Year for Marine Le Pen and the Front National as the news of the Charlie Hebdo and hostage killings undoubtedly garnered further legitimacy for the right wing party she heads. On the one hand, Le Pen seemed to stray from xenophobic hints by thoughtfully labelling the abhorrent acts as the work of “extreme Islamic fundamentalism.”[1] On the other, her assertion that “denial and hypocrisy are no longer an option” left her words purposely vague over who really is to blame for such a tragedy. Indeed, Le Pen’s rhetoric underpins a larger polemic on the role Islam, as an ideology, plays in cultivating such acts of terror.

French police forces have stormed a Jewish supermarket in Paris at the bludgeoning price of four more innocent lives. The Front National will point to the failure of multiculturalism in France, (and in Europe for that matter), their mantra as they swept to European Election victory last year); however, it will not stop there. Underneath this lies a specific victim of Western fury: Islam and the Islamisation of Europe. A religion, La Pen has argued before, incompatible with France’s ‘enlightenment’ and promotion of secularisation.[2]

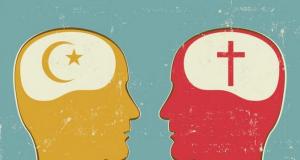

At a superficial glance, the perpetrators of this tragedy have clearly targeted a political satire magazine that laughed in the face of reverence to their religion’s Prophet, and so, by definition, these attacks are clearly religiously orientated: free speech and personal sovereignty versus religious piety and submission to supernatural deity. However, whilst this is not an earth shattering concept, let us one more time assert that the difference between Islam and Islamism is stratospheric. The two do not go hand in hand, and it is a myth that being Muslim and exercising freedom of expression are incompatible. This lazy generalisation is precisely the end game such an attack hopes to achieve, to entrench Muslims into an ‘us and them’ mentality, as if the notion of Islam cannot coexist with the values of democratic states.

More than 25 years ago, Salman Rushdie experienced the wrath of the Islamic Republic of Iran as Ayatollah Khomeini’s fatwa essentially rendered the writer the victim of a global game of manhunt. Since then, a globalised audience has viewed or heard of countless acts of violence, terrorism, and intimidation committed in the name of Islam and in protection of its holiness. The one facet these attacks have all had in common: a religious issue, specifically an Islamic one.

However, take the Rushdie example: historians now point to a flailing Khomeini who had lost the revolutionary flame of 1979 after the sordid, dehumanising decade-long conflict with Saddam Hussein as a key reason for this fatwa. A pious publicity stunt aimed at unifying Islamic anger at Western debauchery. Ergo, not personal spiritual, pious factors influencing the Ayatollah but socio-political ones. Indeed, when digging a little deeper, it becomes very apparent that such an explanation is literally compatible with any example of Islamic extremism. If the spiritual or religious element of this extremism was so apparent, why was the fatwa repealed by the same Islamic Republic only 10 years later?

Many will retort that religious elements still remain in the motives of Islamic terrorists, because of religion’s ability to share an apocalyptic message based on an eternal realm not confined to the limits of the present. This utopian outlook seemingly transcends the law of any state and is harder to gauge because it has more scope to mobilise a demographic through promising a heaven-like conclusion. Consequently, terrorist groups “envision establishing a world order as a result of an apocalypse precipitated by their acts of terrorism.”[3] However, again, this outlook supposes that religious motives are the unilateral element in influencing barbarous acts. Al Qaeda’s infamous number two, Ayman Al-Zawahiri, wrote the organisation’s thesis on their outlook toward the West in Knights under the Prophet’s Banner. Commentators again point to the very tangible political aims of Al- Qaeda through this literature- the removal of American forces from the holy land of Saudi Arabia, an end to the Zionist campaign in the Middle East, etc., all very common and regurgitated qualms accentuated in order to recruit the largest demographic possible to their cause. Again, hardly an ‘Islamic’ issue.

Indeed, some scholars will argue that religious extremism does not exist devoid of political concerns. It would not be gratuitous to conclude that the Japanese extremist group, Aum Shinrikyo, are the only terrorists who endeavour toward no political aim due to their motives revolving around bringing a religious apocalypse, beyond the requirements of a political demand: “A mass religious movement motivated by a mystical, almost transcendental, divinely inspired imperative.”[4] Ironically, their mantra contains plagiarised passages from Hinduism, Christianity, Buddhism, Shintoism and mysticism.

The roots of extremism are complex and employ several factors as a key influence. In our globalised world with migration of ethnicities becoming more and more common, a pluralistic view is required for society to function for the benefit of all, as opposed to a few. This is why the difference between condemning Islamism and not Islam has to be candidly apparent. What are we saying of the religion of more than 1.4 billion humans on this earth if we infer that correct interpretation of their religious texts encourage this barbarism?

If there is one poignant reminder of this fact from this harrowing weekend, it is Ahmed Merabet: a French policeman, a father, a husband, a believer in the freedom of expression and a Muslim. The murders at Charlie Hebdo were not in his name, not consistent with his Islam, so much so that he died to highlight that fact. As the West’s eye turns from mourning and solidarity to security and retribution, we would do well to remember that these murders once again highlight the difficulties Islamism provides to its own followers.

[1] http://www.theguardian.com/world/video/2015/jan/08/marine-le-pen-radical-islamism-charlie-hebdo-attack-video

[2] http://www.independent.co.uk/voices/comment/le-pens-attacks-on-islam-are-no-longer-veiled-8181891.html

[3] Bard O’Neill, Insurgency and Terrorism: From Revolution to Apocalypse (Virginia: Potomac Books, 2005), 23.

[4] Hoffman, Inside Terrorism, 119.

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research