15 March, 2020

By Theodora Ogden – Junior Fellow

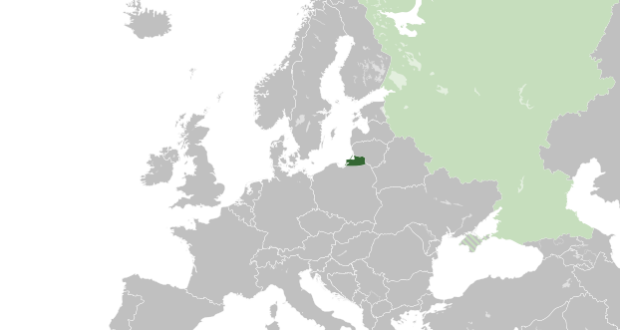

Once part of the USSR’s ‘inner’ empire, after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Kaliningrad became an exclave. Nestled between Poland and Lithuania, the oblast (‘province’ or ‘region’) geographically sits within the confines of the EU bloc but is distinctly set apart. A former Prussian state, and previously part of the German Reich, Kaliningrad is now very much Russian, although it lies some 300 miles west of the rest of the nation, geographically cut off from the capital by Lithuania.

The city has served as an important strategic foothold throughout history. The site was previously home to a 13th century military fortress controlled by the Teutonic Order. Formerly known as Königsberg, the city was targeted by RAF bombers during WWII and most of the historic Prussian architecture and artefacts – according to some accounts the famous Amber Rooms – were destroyed by artillery fire with the advance of the Red Army.

The city was renamed Kaliningrad and the castle was demolished on the orders of Soviet politician Leonid Brezhnev in 1968. The Brutalist House of Soviets was constructed on top of the remains. The foundation of the building sank into the castle’s remnants below, rendering the structure unusable. The building was never finished and has been left abandoned, sparking tales of Prussian Revenge. Kaliningrad, initially planned as a model city, became the symbol of failed Soviet state planning, watched over by the concrete eyesore.

At the 1999 Washington Summit, NATO enlargement plans invited former Warsaw Pact countries Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic into the fold. A few years later, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia became new additions to NATO. Critics of NATO enlargement pointed out that Kaliningrad would become surrounded by NATO forces, prompting Russia’s territory to become a defensive outpost. Indeed, the oblast did not take too well to NATO intervention in the Baltic region. A bar in Kaliningrad famously bore the sign: “No beer will be served to customers from NATO nations”.

Roughly the size of northern Ireland and with a population of less than one million, Kaliningrad is an important military base. It provides access to the Baltic Sea and it is Russia’s only port that remains ice-free all year round. However, Kaliningrad is encircled by EU and NATO member states and their closely observed waters, which means that Russian naval force manoeuvres do not go unnoticed in the area. It is equally unlikely that Kaliningrad is an appropriate base from which to launch aircraft undetected.

The oblast is, however, an ideal location for interception and interference with allied communications, due to its vicinity to capitals and their embassies. Kaliningrad also serves as an early warning system for the rest of Russia in the case of an attack. It is home to advanced Integrated Air Defence Systems, as well as a score of military bases and storage facilities.

Historically, the city has been a key forward base. During the Cold War, the bulk of Kaliningrad’s income was generated by hosting the USSR military. After the collapse of the Soviet Union and a shrinking military presence, the oblast was geographically cut off from the rest of Russia by its neighbours. Formal Soviet trade links and agreements within the region were severed. Kaliningrad was left to enter separate markets: the Russian market, the Baltic market and the EU market.

The ports of Kaliningrad struggled to attract business. Not only were the port authorities unfamiliar with free trade, but the bureaucratic procedures were rigid and time-consuming. Instead, traders would turn to the competing ports of Gdansk, Riga and Tallinn. The subsequent poverty and high levels of unemployment and crime drew concern from nearby states.

In later years, intervention from the Kremlin, in addition to EU support, has improved prospects. Today, some Kaliningrad residents are reported to hope for closer ties to European neighbours despite sanctions on Russia, as well as the restoration of Prussian architectural heritage sites. Home and burial place of Immanuel Kant, the city has potential to become a cultural hub and a “natural laboratory for EU-Russia relations”.

In recent years the territory has become less isolated, even cosmopolitan, and offers a budding tourist spot for those intrigued by its history. While the majority of Russians rarely visit the EU, Kaliningrad residents travel frequently to neighbouring nations. Over 70% of Kaliningrad residents hold a passport, in comparison to a nationwide figure of under 30%.

However, Kaliningrad remains the subject of controversy and international tensions. In 2014, Russia unilaterally imposed a 500-kilometer flight route restriction over the oblast, going against the 2002 Open Skies Treaty (OST). The agreement signed by 34 nations, including the Russian Federation and the United States, permits unarmed aerial observation flights over partner states’ territories.

The United States has responded to the Russian Federation’s violations of the OST with threats to withdraw from the Treaty, which could put an end to military transparency. For now, the US remains a member, in part to maintain transatlantic ties and observation capabilities of Russian military developments and operations. A US exit from the OST could exacerbate international tensions, amid scrapping the Iran Nuclear Deal and the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty.

Some commentators reckon that the highly developed US satellite capabilities mean that the OST is an expensive and obsolete endeavour. Last year, President Donald Trump tweeted an aerial image of the aftermath of an explosion at Semnan Launch Site One at the Imam Khomeini Space Center in Iran, revealing the capabilities of what is presumed to be the highly classified USA 224, a multibillion-dollar KH-11 surveillance satellite launched in 2011. It marked the first time a satellite image of such sharpness was released into the public domain.

While US spy satellite capabilities may significantly outstrip the technology of surveillance flights under the agreement, the OST contributes to three essential elements of peace: security, stability, and verification. The Treaty offers a way for partner countries to share the data collected as well as the costs of surveillance flights. This builds trust and cooperation, particularly among nations without advanced satellite technologies. While the US does not often share the data collected by its satellites – and certainly not without substantial time taken for clearance and processing – images taken by observation flights can be shared more widely and quickly.

Above all, the Treaty provides reassurance to its signatories. Recent activity indicates that Russia is growing increasingly wary of US spy satellite activity. General John Raymond, commander of the United States Space Force reported that two Russian satellites have been following a US surveillance satellite. This incident is sparking concern as it marks the first such confrontation in space.

Kaliningrad lies at the core of the Open Skies Treaty dispute. It has become the permanent home of nuclear-capable Iskander-M, advanced mobile missiles with a range of up to 500 km and the manoeuvring capability to evade anti-ballistic missiles. This development comes as US and NATO forces installed SM-3 missiles in Romania and Poland, reportedly to defend against a potential Iranian rocket attack.

Such action, in addition to NATO exercises manoeuvres along Russia’s borders, have resulted in defensive reactions from Russian authorities. A vantage point to counter threats to the west, Kaliningrad is the key base from which Russia can launch an offensive or intercept attacks. Its strategic importance cannot be underestimated.

However, mounting tensions have a destabilising effect on the region. Furthermore, as a city that is finally starting to rise from its Soviet ashes, Kaliningrad risks remaining trapped between East and West. In 2016, Western sanctions on Russia put an end to the oblast’s decade-long “special economic zone” privileges, which allowed duty-free trade with EU neighbours. This significantly affected the economy, slowing trade and growth. Nonetheless, Kaliningrad has persevered, hosting some matches in the 2018 FIFA World Cup and even becoming a designated tax haven.

Despite Kaliningrad’s rich and complex history, the city’s current aesthetic, economic stagnation and social instability is in need of attention. However, for as long as Russian authorities prioritise its military importance, Kaliningrad’s residents will have to wait.

Image: the Kaliningrad exclave (source: Alphathon/Wikimedia/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research