14 March, 2022

by Sam Biden, Global Leadership Fellow

Current System

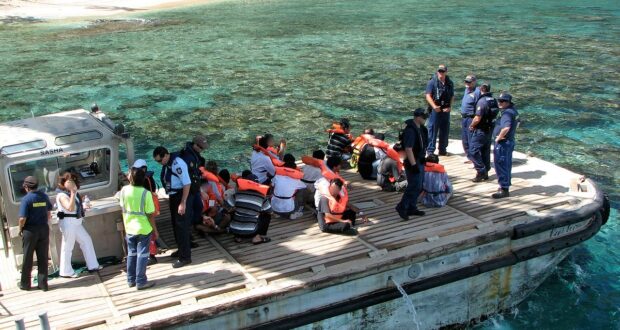

Australia has been incorporating an ‘offshore’ detention system for over two decades. This system is facilitated via the Migration Act 1958 (MA), allowing for indefinite and arbitrary detention. The system initially ran from 2001-2008, and has now been running from 2012-present. This method of immigration relies on the Australian government not holding individuals attempting to enter the state within its own territory but instead doing so elsewhere. These detentions are held in Nauru and Papua New Guinea (PNG). This practice of instant penalisation is a violation of Refugee law, specifically Article 31 (1) of the Refugee Convention. This Article prohibits penalties made against asylum seekers for illegal entry so long as they feel their life or freedom was threatened, they present themselves without delay and have good cause for illegal entry. Many people fled for Australia and surrounding states from Sri Lanka during the declaration of a state of emergency in 2005. However, steep penalties were enforced far before this during the Tampa affair. In 2001, 433 rescued refugees from Afghanistan were onboard a Norwegian freighter that was denied entry to Australian waters. Upon entry, Australian special forces boarded the ship and instructed the Captain to remove the ship and all aboard back to international waters. The UNCHR and International Maritime Organization (IMO) reminded Australia of their obligations, yet they refused to accept this. Days after the instance, Australia passed the Border Protection Bill allowing them to remove any ship from Australian waters with force, including those who attempted to disembark. This escalated further in 2001 with the landing of US troops in Afghanistan, causing further instability for the region. Escaping a war-torn region falls certainly within the notion of a good cause.

In what has been described as a ‘burden-sharing’ arrangement, the international agreements between Australia, PNG and Nauru have a lack of clarity regarding how the agreements work, causing exploitation of the poorer states by the Australian government. This policy has been welcomed by successive Australian governments, all claiming that it acts as a necessary deterrence against people-smuggling and illegal immigration. This ‘necessary deterrence’ has not gone internationally unchallenged – many communications to the ICC (International Criminal Court) have been made regarding what they claim as crimes against humanity. National claims in Australia have been made against these methods of detention as well as a series of claims in PNG that resulted in the Manus Island detention centre being deemed unconstitutional for its restrictions on freedom of movement.

Since 2001, over 5,800 refugees and asylum seekers have been detained under the program and subsequently fallen victim to horrific conditions in offshore detention. As of March 2021, 240 people, many of which are officially recognised refugees, remain in Nauru and PNG. Larger numbers once filled the detention centres but after a major wave of self-deportation out of desperation for a better life, many of these returned to their own state, regardless of any potential dangers awaiting them. Australia has managed to secure many high profile contracts with third-party security forces to keep the detention centres secure. Most notable is the world’s largest security firm, G4S, the same company widely accused of racial misconduct and the assault and abuse of detained individuals in detention centres they were contracted to maintain.

Submission to Joint Standing Committee on Migration (JSIM)

The JSIM is an Australian government joint committee comprised of both the House of Representatives and the Senate. The JSIM was established to deal with migration based issues. In June 2021, the Selection Committee referred the Ending Indefinite and Arbitrary Immigration Detention Bill to them. The bill has now been introduced, and the JSIM is accepting submissions about any inquiries to do with the proposal. including the new A long-standing NGO, Amnesty International, made a submission to the Joint Standing Committee on Migration, outlining their concerns. Under the MA, asylum seekers and refugees are detained to await their immigration hearings. The only two methods that allow for this detention to end are; if the claim is successful, in which case a visa is granted, or the claim is unsuccessful, resulting in refoulement/deportation. Because of a lack of independent review regarding each case, there is a possibility that detained people will have to remain indefinitely. In some cases, the review of a claim can take up to 5 years. During this period, the claimant is bound to be detained. This waiting period is exacerbated by poor procedural safeguards in Australia, resulting in errors in decision making and a lack of legal advice and representation for each claimant.

In 2019, Amnesty International Australia (AIA) went to PNG to gather testimonies and evidence from those who had fallen victim to offshore detention. Many of the people they interviewed described how they and their families were subjected to physical and mental abuse, as well as sexual assaults. The healthcare they were given was totally inadequate. Medical services, specialists, tests and procedures were almost completely inaccessible. This means that if you fell ill while in these detention centres, the likelihood of aid is near non-existent. This has resulted in over a dozen deaths of refugees and asylum seekers. AIA further found that commitments made by the Australian government to uphold their obligations under the Convention against Torture (CAT) and its optional protocol had crumbled. The two primary states of New South Wales and Victoria have not so far implemented these obligations. Since Australia’s immigration system is handled at the federal level, the fact this has not become federal law to force the remaining regions to adopt the measures is a major cause for concern. After this visit, AIA went on to produce a heartbreaking report about conditions in the other detention state, Nauru.

‘Island of Despair’

1. Attacks testimonies

There are countless instances of violence being committed against refugees and asylum seekers in Nauru. One man was attacked by a group of men, they beat him with a rock and then stole his motorbike. A young Somali woman’s husband was attacked by a group with machetes, they later broke into the accommodation they were being housed in. An Iranian woman witnessed another woman be beaten over the head with a metal pipe in the streets, she had to receive eight stitches in hospital. Two Iranian men were kicked off a cliff by locals when they were approached and asked about cigarettes, both men have permanent injuries from the impact. Worst of all, a man was beaten so badly that he had to be transferred back to Australia as it was deemed he was no longer safe in the state they sent him to initially.

As well as attacks, AIA found numerous instances of threats of physical violence towards refugees on Nauru. AIA claim these have not been investigated by the Nauru Police Force. In a flood of social media posts, many women who were victims of rape during their detention were claimed to have not “come up with on (sic) single evidence to proving their allegations”. An anonymous threat posted stated: “This is a warning to all refugees and asylum seekers in Nauru. We the Nauruan people are not intimidated. Do something stupid and Nauru will come to you and your entire family on the island and the police will not stop us.” Threats like this have also been made from the Nauruan police officers and security employees of Transfield, who have a similar contract to G4S.

2. Children’s rights violations

The first child protection legislation in Nauru was passed in 2016. Nauru does not have any consistent reporting, data collection or monitoring in relation to child maltreatment in their facilities. Nurses and doctors have little training to help them identify either family mistreatment or child abuse in the facilities, health staff are also ‘unclear’ whether to report cases they do find. From this, no statistics are available at either the hospitals or Public Health Centre regarding child neglect. When children are given some form of treatment, there is rarely ever any follow up to check on their wellbeing.

This has caused grave concerns over the safety of the children. The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC) raised major problems with Article 19 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child. This Article states that State parties shall take all appropriate measures to ensure; the safety and wellbeing of the child, including freedom from physical or mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect or negligent treatment and maltreatment or exploitation. The CRC’s findings paint a harrowing picture. They found persistent discrimination against asylum-seeking and refugee children in every area. Firstly, the Nauruan police have a very limited capacity to investigate allegations of sexual-based violence against children. This is corroborated by the fact 30% of female victims had suffered sexual abuse before the age of 15. Successful cases made against the perpetrators resulted in sentences that were far from the recommended legislative sentencing. The issue is worsened as staff in a Regional Processing Centre have been repeatedly accused of sexual misconduct, assault and rape. The Moss Report, a detailed analysis of conditions in these centres gathered many testimonies from victims, some as young as 11 and brought these issues forward. Secondly, evidence of inhuman and degrading treatment, including physical, psychological and sexual abuse against asylum-seeking and refugee children residing in the Regional Processing Centres. Physical mistreatment has come in various forms. One young child was hit on the back of the head by a guard, another was threatened with a cricket bat while a third was physically harassed by a guard to the point he suffered severe bruising. Psychological trauma has caused a spike in self-harm and suicide attempts by many children in the facilities. From October 2013-14, 17 minors were recorded for self-harm. One 16-year-old attempted suicide by hanging, while others swallowed dangerous objects such as rocks and washing detergent as a form of self-harm. It is profusely clear that the rights of minors were not even remotely upheld during their detention in these facilities.

New hope for victims

While the horrors of the last two decades still haunt those victims, redress is in motion that will change the course of Australian migration law forever. The Ending Indefinite and Arbitrary Immigration Detention Bill is currently going through the Australian Parliament. There are a total of 23 clauses, of which 7 are groundbreaking.

- Clause 9 (Principle of the rights and best interests of the child): This clause ensures that all actions taken through the act will have the best interests of the child in mind. This could lead to ensured prosecution of perpetrators against minors, as well as the establishment of better reporting and monitoring systems designed to target neglect. As seen previously, third party handling of these matters proved dangerous to the health of minors, this will now hopefully change that.

- Clause 10 (Relationship with other laws): This overrides previous Australian legislation that was used to justify offshore detention, particularly the MA. From this, the legislative basis for the agreements with PNG and Nauru can become legally void.

- Clause 11 (Immigration detention): By far the most important clause, this guarantees the fundamental rights of liberty and security of the individual, something severely lacking in the prior agreements. 11 (1) prescribes that detention may now only take place within Australia, additionally, this detention can only be arranged when a legitimate purpose has been determined that is both necessary and proportionate to each individual case. This focus on individuality is directly in-line with Australia’s international obligations. An individual assessment of each asylum request must occur as collective expulsion is a violation of refugee law. This objective assessment clause echoes international law jurisprudence.

- Clause 12 (Detention alternatives): If detention arrangements in clause 16 cannot be fulfilled, then alternative arrangements can be made. Per 12 (2), this can mean communal arrangements as opposed to detention, such as supported housing. This is a much more beneficial structure than guaranteeing detention for every individual, it will also help mitigate abuses from staff in detention facilities.

- Clause 13 (Access to assistance in alternatives): This clause directly implements Article 24 of the Refugee Convention. This ensures that social security shall be provided to refugees on the same level as done to Australian citizens. This clause also confirms the right to work, and that detention living shall offer the same support and services as communal living. This is a drastic shift from the previous arrangements, direct conventional citation for legislation solidifies the now positive intent of the Australian government.

- Clause 16 (Reasons for immigration detention): This clause guarantees in accordance with the Detention Guidelines from the UNCHR. From this, there are four primary grounds for detention that must be used only for a legitimate purpose. These are; protection of public order, health or national security. For example, one can see why a flagged terrorist associate can be detained after unlawfully entering Australia, yet this would now not apply to those fleeing persecution, such as asylum seekers from Sri Lanka.

- Clause 21 (Children in Detention): This child-specific clause allows for three major changes. First, detention of children must be used as a final measure after all other arrangements have failed, or are not applicable. Second, the ‘best interests’ principle is now the paramount objective of the State, from this, separation from family and detaining in arbitrary conditions that are similar but not exactly the same as those in PNG or Nauru is banned. Third, a general rule for unaccompanied minors states they should not be detained and that their circumstances must be promptly handled by a Federal court.

In what began in 2001 as a series of agreements to implement Draconian legislation, new hope in the 2021 bill demonstrates a new motion for immigration in Australia. No longer will there be an automatic assumption of malice on the part of the innocent seeking refuge, but a system of sympathy aimed at meeting their basic fundamental human rights, including security in their new lives.

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research