July 22, 2019

By Irena Baboi – Senior Fellow

On 31 March, the Turkish opposition celebrated what nearly became a short-lived electoral and political victory. Ekrem Imamoğlu of the Republican People’s Party (CHP) narrowly defeated Binali Yıldırım of the governing Justice and Development Party (AKP) in the municipal elections, and became the new mayor of Istanbul. Less than five weeks later, in response to calls by the AKP for a rerun, the centrally controlled electoral board overturned the results, citing irregularities during the ballot counting. When the new vote was held on 23 June, not only did Imamoğlu win again, he won by an even greater margin, making his victory the biggest electoral win of any Istanbul mayor in thirty-five years. Anxiety and outrage rapidly turned into hope and optimism both within and outside of Turkey – and for the first time in years, change no longer seems an unrealistic dream.

The Istanbul rerun marks the ninth election experienced by the city in the last five years, as since 2014 the people of Turkey have voted in two presidential, three general and two local elections, and a referendum which replaced a century-old parliamentary system with executive presidency. Despite this, turnout stood at 84.5 percent on voting day, proving once again that an overwhelming majority still believes in democracy, and is prepared to defend it. This high turnout, moreover, is not uncommon for Turkey, as even their lowest rate in decades – 74 percent in the 2014 presidential elections – is still significantly higher than that of many full-fledged democracies.

Voter mobilisation during the rerun, on the other hand, can be characterised as exceptional. Driven by resentment and a sense of injustice, the people of Istanbul were quick to organise to ensure that their political choices would not go ignored. From the moment the rerun was announced, holidays were cut short or cancelled altogether, and funds were raised to help students return to Istanbul – and voters of all ages and physical capacities made their ways to the polling stations to exercise their democratic right.

In a country where elections are far from free and fair, this is a remarkable win for democracy. Equally remarkable is the fact that, despite the game being rigged against them, the opposition is now in charge of Turkey’s three largest cities: Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir. For over a decade, opposition parties in Turkey have had limited access to public space and airtime during political campaigns, and critics of the government have faced silencing and intimidation in the form of defamation lawsuits and terrorism charges. While the ruling elite has been careful not to interfere with the voting and vote counting themselves, it has done all it could to ensure the opposition is both under and misrepresented in the media, and thus does not constitute a viable threat.

Aside from a deep sense of unfairness, what also drove voters to support the rival to the AKP’s candidate was Ekrem Imamoğlu’s positive and conciliatory campaign. Dubbed “radical love” by his Republican People’s Party, Imamoğlu ran on a message of inclusion and togetherness, the polar opposite of Erdoğan’s quest to deepen religious and cultural divisions in Turkish society. The CHP’s campaign also centred on improving welfare, delivering better municipal services, reducing waste and ending corruption – and restoring democracy in a country where freedom of expression, information and assembly are severely constrained.

The rerun of the Istanbul election was deemed an uncharacteristic miscalculation by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Turkey’s most successful politician since founding father Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. It remains unclear whether it was overconfidence in his ability to change people’s minds that drove him to this decision, or the importance of Istanbul that made him unwilling to allow someone else at its helm. The economy of Turkey’s largest city accounts for a third of the country’s GDP, and the AKP has taken advantage of Istanbul’s vast municipal budget to fund lucrative infrastructure contracts with government-friendly companies. The opposition now has access to the paper trail from these contracts, which means that any evidence of corruption or wrongdoings is now in their hands.

The unfortunate reality, however, is that Imamoğlu’s win does not come with a free-hand in all things political and economic. As an all-powerful executive, Erdoğan can end Imamoğlu’s mayoralty at any moment, and elected mayors in general have limits imposed on their financial resources and authority. As such, a lot depends on how Erdoğan is going to react to this result in the long-term – snap elections are not only far from uncommon in Turkey, but also a tried and tested strategy for the ruling elite to get their own way.

In the short-term, the Turkish president seems to have dismissed the loss as unimportant, as would any leader confident in his grip on power. As things stand, there continue to be no meaningful checks on his presidency, the judiciary remains politicised, and the media is almost entirely under government control – and Erdoğan does not have to stand for re-election until 2023.

The five-year road ahead, however, is likely to not be as easy as it first appears. Increasingly dissatisfied with Erdoğan’s growing control over the party and government, two founding members of the AKP – former deputy prime minister Ali Babacan and former president Abdullah Gul – are reportedly planning to form a rival party by the end of this year. This is bad news for the AKP’s political standing, as it is already relying on a coalition with the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) to hold a parliamentary majority in the country. The rumoured breakaway party is likely to mirror the early years of the AKP, and combine an Islamic-rooted outlook with a pro-Western, democratic and liberal market approach.

This is the very problem that was highlighted during the elections – both the AKP and Erdoğan himself have strayed too far away from their original rhetoric, leaving both with scarcely any room to grow politically. Erdoğan’s half-hearted attempt to reach out to Kurdish voters fell on deaf ears after over a decade of attacks against them, and even this lukewarm inclusion upset their nationalist coalition partners. The Turkish president’s divisive populism also does nothing to address voters’ financial and material concerns – the growing unemployment and rising food prices, coupled with difficult relations with the West and potential US sanctions, are matters that cannot be solved by casting the blame elsewhere.

Much like in the case of any populist leader, Erdoğan’s political games only work in times of economic growth and when his party stands firmly behind him, but also when he’s playing them against a fractured and divided opposition. Turkey’s municipal elections showed that the opposition, despite their broad differences, are more than capable of coming together and standing united against the governing elite. The elections also showed that Erdoğan has lost touch with his people – and the way things are going, it will only become more and more difficult for him to adapt his politics to their needs.

Above all, the Istanbul rerun and its outcome represent an important lesson in countering populism and its proponents. Imamoğlu’s politics of openness and unity, along with his pragmatic approach, spoke to a people weary of arguments and belligerent rhetoric, as well as a divisive discourse that has done nothing to improve their quality of life. In an atmosphere of exclusion and injustice, Imamoğlu emerged as a breath of fresh and positive air – and Istanbul’s new mayor is the only political figure that stands a viable chance of dethroning the current authoritarian powerhouse.

In the short-term, Turkish politics are unlikely to experience radical change, as Erdoğan has created a system for himself that will not be easily pried from his grasp. In the long-term, however, the cracks in his grand design will become too numerous to handle – and people’s living conditions are not made better with talk of isolation and strife.

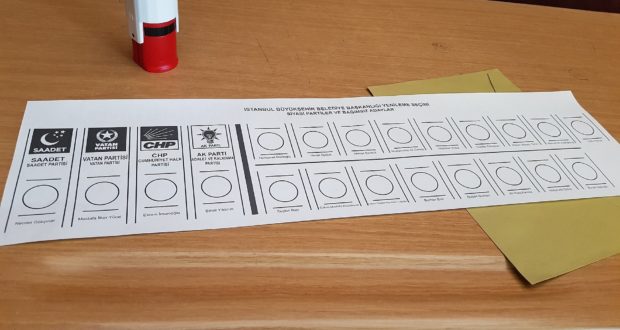

Image: June 2019 Istanbul mayoral election ballot (Source: Sakhalinio)

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research