26 October, 2020

By Ataa Dabour – Research Assistant

Since the end of the Cold War, we have witnessed a powerful comeback of the so-called “privatization of security” or the “outsourcing of military functions”. In other words, private military and security companies providing support for military operations – most often in the form of defensive security, training for national forces, and technical support. The number of these companies has been continuously increasing. A 2016 analysis of the market of the private military companies (PMCs) in armed conflict shows that more than 1,500 PMCs operate in conflict areas, from Africa to the Balkans to the Middle East.

As insecurities are rising around the world, we need responsible commercial security providers more than ever. But the lines between economics and warfare are very narrow. Although contractors are often originally experienced military soldiers, their main objective is to meet the mission given by the client who has contracted them. In other words, they are less likely than members of national armies to be asked to consider the implications of their behaviour – be the impact local communities, human rights or on their state of origin, and instead are led by the need satisfy a client in exchange for financial reward.

In 2006, the UN Human Rights Council investigated the recourse to PMCs and its consequences regarding human rights violations. In doing so, it entrusted the UN Working Group on the use of mercenaries “to monitor and study the effects of the activities of private companies offering military assistance, consultancy, and security services on the international market on the enjoyment of human rights”.

To ensure that human rights are not violated by PMCs, the first report of the UN Working Group concluded the Governments of states from which private companies export or import military assistance, consultancy, and security services should :

- Adopt relevant legislation, set up regulatory mechanisms to control and monitor their activities including a system of registering and licensing which would authorize these companies to operate and to be sanctioned when the Norms are not respected.

- Establish regulatory mechanisms for the registering and licensing of these companies to ensure that the import of the services provided by these private companies neither impede the enjoyment of human rights nor violate human rights in the recipient country.

Allegations of Human Rights Violations

During the US-led Iraq War, a major scandal erupted over prisoner management at Abu Ghraib prison. This management was entrusted to the US military and contractors. Many allegations relating to repeated rapes and inappropriate use of force such as beatings against prisoners were made against PMC Titan (now known as L-3). Several prisoners explained that they were forced to remain naked for long periods or to drink water until they vomited blood. According to an Army investigation into Abu Ghraib, 36 percent of the time that inmates were abused by guards, they were abused by contractors.

But while many of the American soldiers involved in these violations were punished, the contractors who were mentioned in the very same Army investigation report were not. Baher Azmy, the former detainees’ lawyer and legal director at the Center for Constitutional Rights confirms that “private military contractors played a serious but often under-reported role in the worst abuses at Abu Ghraib.”

One of the most high-profile incidents of the Iraq War involved the PMC Blackwater (now Academi). On 16 September 2007, one of their convoy of PMCs guarding State Department employees entered a crowded square near the Mansour neighbourhood in Baghdad. The causes of the use of force are unclear, as versions diverge. Blackwater contractors claim to have been attacked by armed men and to have responded to the attack following procedures and rules of engagement. In contrast, Iraqi police and witnesses report that the contractors fired first on a small car driven by a couple with their child who did not move away from the convoy while traffic was slowing down. Iraqi police and army personnel also became involved in the firefight which ultimately ended in twenty civilian deaths.

These killings were described as a crime by the Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki. Despite this, the Iraqi government could not withdraw the license from contractors for two main reasons. Blackwater had neither a mandate nor a license with the Iraqi government, but instead sourced its legitimacy from the previously dissolved US government authority in Iraq. Second, the contractors were exempt from Iraqi law due to their unclear legal status.

Empowerment as a Method to ensure Human Security

Private military and security industries center around a complex dynamic of economic motivation, as well as political and military requirements. But human rights should also be a major consideration. Whilst the reaction of many to the human rights scandals surrounding the sector is to restrict or outright ban their activities, a more viable path is the empowering of PMCs through implementing educational measures, as well as monitoring and accountability mechanisms to reduce human rights violations and to ensure better human security.

The need for accountability for human rights abuses can be seen in the case of Russian military companies such as Sewa Security stationed in Central Africa. This company work in collaboration with local governments to provide security services to gather intelligence and train local armies, and has had allegations of torture levelled against it. But in the case of human rights violations, who is responsible? The Russian government, the hosting government, the private military company, or some combination of entities?

The lack of accountability comes also from the lack of recognition of the International Criminal Court jurisdiction by the biggest powers and majority of permanent members of the Security Council. Since most private security companies operating in complex situations are registered in the United States and Great Britain, international criminal jurisdiction cannot be applied. Therefore, human rights violations that constitute war crimes or crimes against humanity can be prosecuted only by national courts.

In practice, even though L-3, Blackwater or Sewa Security have been aledged to have been involved in human rights violations, none of them has been significantly sanctioned. Companies contracted by states use the argument of Government contractor defense, which consists of hiding behind a government to not be held liable for their violations.

So, implementing an international instrument, such as a convention, that binds national jurisdictions to take private military and security companies accountable for their acts is fundamental. The binding international instrument should consider all actors that use contracted security services, as well as private military and security companies themselves.

While the role of both a contracting state and a private security industry is to give information concerning the mission to define how security should be applied in conflict areas, to monitor possible dysfunctions, and to ensure compliance with the applicable rules and methods, implementing a monitoring mechanism is a challenge for multiple reasons. Notably, contracts with private military and security companies do not have the usual control mechanism of the free marketplace. According to the American political scientist, P.W. Singer, “the competition is fragmented and the sanctions that could be applied to a contracted company or employee are limited”. Additionally, those who procure their services rarely have a background in procurement, which can lead to challenges in identifying and securing delivery requirements and in doing so forming appropriate monitoring and sanction mechanisms. For example, the US General Accounting Office (GAO) reported that effective oversight of the U.S. military’s Balkans logistics contract was undermined by insufficient personnel training. The lead contracting officer had indeed no contracting background. Both of these issues serve to limit the influence contracting authorities have on PMC training and activities once deployed. There is also the fundamental risk that a contractor may simply have no care for respecting human rights or – at the most extreme – may view PMCs as a pathway to violating such rights in a manner that allows them to escape accountability.

Cognizant of the limits of monitoring, education becomes critical. Private military and security companies have a strong technical and security culture. But they lack human and humanitarian indicators to rely on. This shortfall contributes to widening the gap between security and human rights considerations, and to increasing possible human rights violations. Thus, educating security professionals on human rights and humanitarian law can contribute to reducing violations and insecurities.

Switzerland understands this very well. Faithful to its human and humanitarian principles, the Swiss Federal Council published in 2015 the Ordinance on the Use of Private Security Companies, which confers an obligation on Swiss private security companies to appropriately train their employees. Indeed, article 5 of the Ordinance stipulates that “the contracting authority shall ascertain that the security personnel of the company has received adequate training that is commensurate with the protection task assigned to them…”. Based on the training requirements according to the Federal Act on Private Security Services Provided Abroad (PSSA), the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs assesses if the private security company’s staff is sufficiently trained to be deployed or not in a crisis country. Otherwise, no private military and security company can deploy its personal abroad.

Empowering is a way to raise awareness amongst private security professionals of their human nature and condition, their industry problems, their practices, and to allow them to develop the necessary knowledge and means to make choices and change their methods to enhance human security. By empowering the private military and security companies through the implementation of internationally binding instruments and educational measures, we give them the necessary knowledge, ability, and means to understand that respecting human rights is a fundamental part of their work, as well as the possible consequences when human rights are violated. Giving PMCs guidance would encourage them not only to behave better, but also to reduce reputational and legal risks, and to increase their resilience.

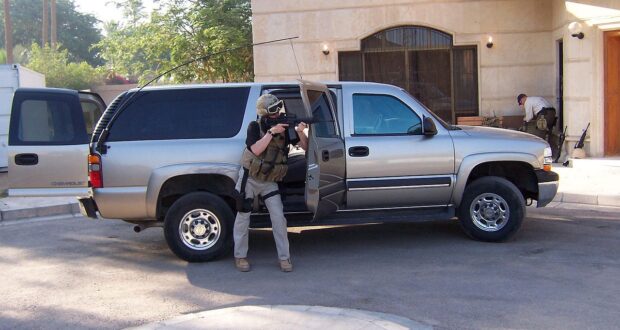

Image: Contract security in the International (Green) Zone of Baghdad, Iraq (Source: Jamesdale10 via CC BY 2.0)

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research