9 April, 2021

By Jack Davies – Junior Fellow

So-called ‘emerging technologies’ are fast becoming a prominent topic of research within the study of war and warfare. Additive manufacturing, artificial intelligence and machine learning, biotechnology, electro-magnetic spectrum technologies, human-machine interfacing, hypersonic missiles, quantum enabled technologies, advanced robotics and many more have been described as ‘game-changing’ technologies, set to radically redefine what war is and how it is fought.

Yet despite fast becoming a central focus within military affairs, the term ‘emerging technology’ is rarely defined within literature. Far too often, authors instead rely on references to a ‘grab-bag’ list of specific technologies to illustrate what they mean by ‘emerging technologies’, for example in this otherwise excellent analysis by Regnault and Kosal, or in Congressional Research Service report R46458. This ‘know-it-when-you-see-it’ approach is simple and effective for authors, especially in the lack of any authoritative definition, but it frustrates and undermines efforts for robust analysis and potential regulation.

Through a series of three observations, this article builds on previous work to shape the contours of both how the terms ‘emerging’ and ‘disruptive’ are currently used within literature, and how they might be more accurately defined and adopted going forwards. It offers a more deliberate set of terminology, accompanied by definitions which centre technology and its impact within the complex socio-technical systems that construct war and warfare.

‘Emerging’ vs. ‘disruptive’

The first observation is that the terms ‘emerging’ and ‘disruptive’ are often used interchangeably, so much so that the distinction between the two – invaluable from a conceptual standpoint – is rendered meaningless.

A prime example of this is Rotolo, Hicks and Martin (2015), who attempt to find a comprehensive definition of ‘emerging technologies’ by synthesising key characteristics emphasised in various literatures. Their definition points to 5 core traits:

‘a (i) radically novel and relatively (ii) fast growing technology characterised by a certain degree of (iii) coherence persisting over time and with the potential to exert a (iv) considerable impact on the socio-economic domain(s) […] Its most prominent impact, however, lies in the future and so in the emergence phase is still somewhat (v) uncertain and ambiguous.’

We see these characteristics emphasised repeatedly in articles and reports on emerging technologies, especially the potential for a prominent, yet uncertain, impact. The Arms Control Association refers to ‘far-ranging consequences’ that, while ‘not yet widely recognised’ could ‘transform every aspect of combat, while the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) stress that while the impact of emerging technologies is ‘not yet fully understood’, they are ‘expected to bring social transformations on an unprecedented scale’, and to exert ‘disruptive effects on the conduct of warfare’.

This is to be expected – Rotolo et al. undertake an excellent and thorough analysis, but in distilling their definition from others’ use of the term, the authors effectively reproduce the systemic error of associating ‘emerging’ with ‘disruptive’. Seeking to define a term by examining its use only serves to codify the flaws commonly embedded in that use.

Pointing to a ‘transformative’ or ‘disruptive’ impact ascribes a meaning to the term ‘emerging’ that isn’t warranted. Rotolo et al. themselves limit their definition of ‘emergence’ to ‘the process of coming into being, or of becoming important and prominent’, which is not synonymous with ‘exerting a disruptive or transformative influence’. A more appropriate term for technologies with a potentially disruptive impact would be ‘disruptive technologies’, or, for those technologies that are both emerging and that promise to have a disruptive impact – ‘emerging and disruptive technologies’. This, incidentally, is the label used by NATO, which established the ‘Advisory Group on Emerging and Disruptive Technology’ in 2020 to facilitate its development and adoption of these technologies.

It may seem pedantic to insist on the distinction between the two terms. After all, most commentators appear to use ‘emerging technologies’ exclusively to refer to those emerging technologies that also have the potential for a disruptive impact – analysts, scholars and policy makers simply aren’t interested in those that don’t. In this sense the term serves its primary purpose – acting as a common reference point that both the user and audience can rely upon to orient themselves in the discussion.

Conceptually, however, this is not enough. ‘Emerging’ and ‘disruptive’ are not synonymous. Not all emerging technologies are disruptive, and not all disruptive technologies are emerging. Making this distinction explicit within the terminology forces us to focus on what exactly it is about any given technology or collection of technologies that we feel warrants attention. Does it matter if a technology is emerging? Or does it matter if it is disruptive?

Technologies in war and warfare

This is the second major observation – technologies don’t exist in a vacuum, and to analyse them as distinct or independent from the societies in which they are imagined, developed, deployed and applied not only leads to incomplete understandings of the technologies themselves, but makes it impossible to have any meaningful discussion of their potential impact.

Jabri (1996) conceptualises war and violent conflict as ‘social phenomena, emerging through, and constitutive of, social practices’. This is a highly valuable starting point, but in order to better analyse an ever-evolving construct within which multiple semi-independent factors constantly converge, diverge and re-converge, we need to adopt the concept of ‘socio-technical systems’.

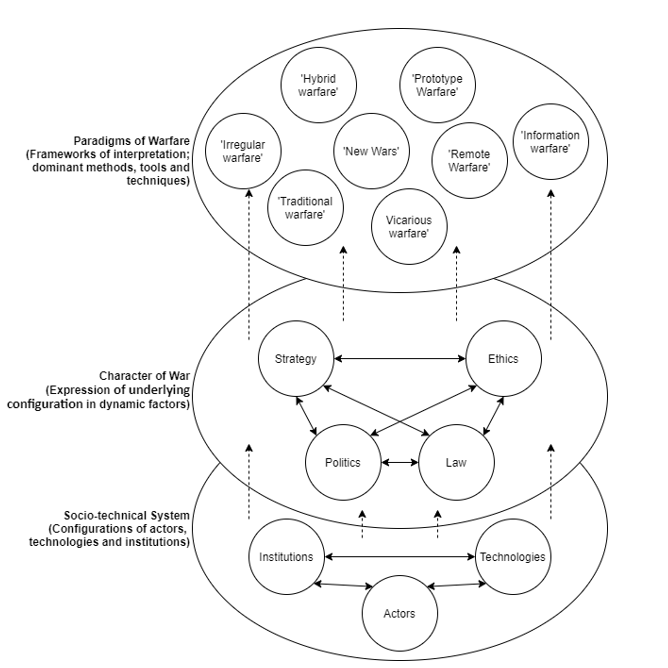

Socio-technical systems are ‘configurations of actors, technologies and institutions’ created for the provision of societal functions, for example energy, mobility or food. (see Schot & Kanger, 2018 for more on this). Essentially, these are the broader paradigmatic and material infrastructures that underly both how a phenomenon is understood and how it manifests within the real world. Socio-technical systems are constantly evolving, reproducing and reworking themselves through both changing imaginaries (sets of values, institutions and frameworks through which individuals and societies conceptualise a social construct) and institutional forms.

When it comes to war, the manifestation is often referred to as the changing ‘character’ of war (coined by Carl von Clausewitz in opposition to war’s enduring ‘nature’ as a violent, interactive and fundamentally political endeavour). It is the real-world expression of the underlying socio-technical system, the way that various bodies, objects, ideas and practices that we experience as ‘war’ display. Put in a more recognisable way, the character of war is shaped by numerous dynamic social factors, including law, ethics, culture, methods of social, political, and military organization and, of course, technology. Finally, these factors converge and coalesce into ever-evolving paradigms of warfare, meaning the frameworks of interpretation, dominant methods and strategies, tools and techniques that characterise the application of ‘war’ as a social tool.

It is difficult to exhaustively list all of the dynamic social factors relevant to constructing ‘war’, however, it is possible to crudely identify some of the major ones: namely strategy (methods, tools and techniques, including doctrine, force structure, tactics), politics, law and ethics. Each of these, being reflections of the configuration of the underlying socio-technical system, shape and are shaped by the others.

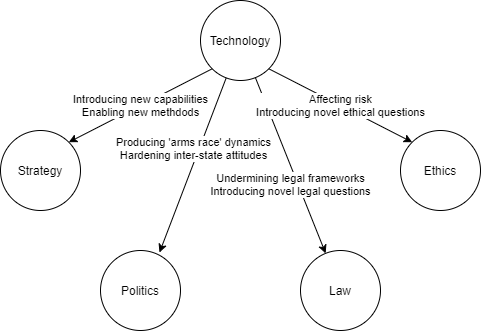

The more closely you consider these factors and the relationships between them, the more it becomes clear that extracting any single one and operationalising it as a purely independent causative driver of change is, at some level, impossible. Nonetheless, technologies appear to be driving change in war and warfare in ways that, while not necessarily new, are perhaps more readily perceived than ever before. How can we conceptualise the role that technologies play in changing war? Through what dynamics, infrastructures, interactions and relationships does technology influence the character of war?

Applying the above theoretical approach, we can conceptualise this influence as follows:

Technological innovations adopted within the socio-technical system adjust the configuration of actors, technologies and institutions that define it. In turn, the expression of this underlying configuration changes within dynamic social factors, specifically strategy, politics, law and ethics. Finally, newly adapted social factors diverge, converge and re-coalesce into new paradigms of warfare, and the cascade of impact is complete.

To focus in on this causative chain and to simplify our description of the process:

Technologies exert an impact on the character of war by influencing strategic, political, legal or ethical affairs.

This is the key to understanding, defining, and identifying disruptive technologies; considering which features of any given technology might influence these factors, in what way, and to what extent. Considering the potential impacts of any given technology on these factors provides analysts an easy, if crude, way of recognising the extent and importance of that impact. Yet we still need a way to identify at what point this impact can be characterised as ‘disruptive.’

Here the concept of a ‘revolution in military affairs’ (RMA) offers a useful analytical lens. At the risk of over-simplifying a much debated and hotly contested term, an RMA is a discontinuous change in military affairs. It is a point at which an abrupt (though not necessarily instantaneous) and fundamental change, catalysed by the emergence of some factor external to the prevailing wisdom or practices of the time, occurs within war and warfare, challenging and replacing the previous dominant state-of-affairs. The RMA provides a valuable analytical tool to describe the manifestation of influence as disruption – that of ‘discontinuity of affairs.’

To introduce this into our terminology:

‘(Emerging) disruptive technologies impact the character of war by changing the configuration of actors, technologies and institutions within the socio-technical system, affecting a discontinuous change in strategic, political, legal or ethical affairs.’

In predicting the influence of any given technology on any given factor there is still significant scope for uncertainty. Many analysts working on disruptive technologies are given to implicit technological determinism, presenting potential impacts in certain terms, as if predetermined by the nature of the technology itself. This, however, is mistaken.

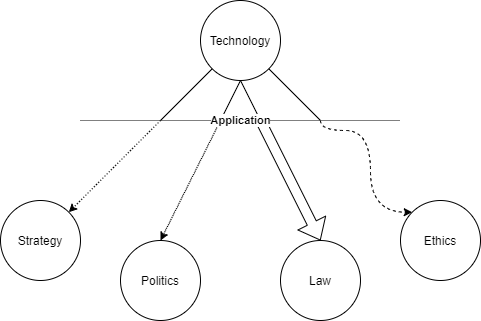

The choices people make matter

This is the third observation – technologies exert an impact through their application, and their application is the result of the choices their developers, deployers and users make. Titan II missiles can be used to deliver nuclear warheads, but they also sent Gemini astronauts to space; the internet has been transformative in connecting human beings across the globe but has also been used as a tool of mass surveillance and oppression; a drone can be used to perform signature strikes outside of armed conflict, or to search through inaccessible or dangerous areas for missing persons.

What matters is not only the capability that a technology affords actors and institutions within a socio-technical system, but how that capability is exercised. It is only through this application that a technology influences strategy, politics, law and ethics. It is a gateway, a mediating influence that determines the nature of an impact on a dynamic factor.

As ‘It’s not the technology, it’s what we do with it. And the more sophisticated the technology gets, the more important the people get.’ – Jon Lindsay

Some scholars have argued that application is so fundamental to a technology’s impact that analysts should use the phrase ‘technological applications’ instead of ‘technologies’. Within the present discussion, this brings us to:

‘(Emerging) disruptive technological applications impact the character of war by changing the configuration of actors, technologies and institutions within the socio-technical system, affecting a discontinuous change in strategic, political, legal or ethical affairs.’

Stressing the importance of application is not just an academic exercise – it has implications for how policy makers might approach regulation. If regulating capability by restricting the development of a technology is not possible, practical or realistic (as is the case with many dual-use technologies), then regulating that technology’s application by restricting actor behaviour may be an effective route towards shaping the impact it will have.

There is one important caveat to this argument: when discussing emerging technologies (disruptive or not), the potential applications of the technology are, by their nature, uncertain. In these cases, it may be more appropriate to avoid emphasising their application as the central factor for their importance. I would argue that both ‘(emerging) disruptive technological applications’, and ‘(emerging) disruptive technologies’ are valid, so long as they correspond to a sufficiently well-defined subject of discussion (e.g. CRISPR, the emerging disruptive technology; genomic and genetic engineering, the [emerging] disruptive technological application).

The bottom line

Ultimately, no matter how these terms are used and regardless of the precise framing of their definitions, what is most important is that the user clarifies their interpretation and application.

What exactly do ‘emerging’ and ‘disruptive’ mean to the user? Within what context are these technologies emergent or disruptive? Which aspects of those labels are being emphasised as most central to the analysis? In what ways do the subjects under analysis fit the definition used, and in what ways do they not?

A ‘know it when you see it’ approach to ‘emerging and disruptive technologies’ may be easier than taking the time to outline its meaning, but it only serves to frustrate efforts for comprehensive analysis and eventually regulation. At a minimum, and even if it is only surface deep, users should take the time to clearly set out at least a basic definition.

Image: BigDog robots (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Lance Cpl. M. L. Meier)

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research