6 January, 2022

By Jack Davies – Junior Fellow

Europe and the EU have a huge amount to gain by adopting a more sustained, long-term and purposeful approach to the space domain. Space is a critical domain across almost all aspects of society, not least of which is security and defence. Space-based assets and their ground-based supporting infrastructure provide crucial positioning, navigation and timing (PNT) services for numerous critical national infrastructures (CNI) and industries, and modern militaries are almost entirely reliant on satellites for command, control and communications (C3) functions. Beyond this, the provision of Earth Observation (EO) services in support of disaster response, environmental monitoring and economic planning represents an important and growing share of space-based services. All told, satellite navigation directly enables roughly 10% of the EU’s collective GDP.

In seeking to develop these capabilities Europe’s space activities have coalesced around a series of ‘flagship’ initiatives, Copernicus, Galileo and EGNOS. Copernicus is a constellation of EO satellites that provide environmental and climatic monitoring services internationally, aiding efforts to tackle climate change, monitor biodiversity and supporting disaster relief. Galileo is perhaps Europe’s most well-known space flagship initiative, offering the most precise navigation data available to over 2 billion users globally. Currently consisting of 26 satellites, it was effectively launched as a European alternative to the US’s GPS system. EGNOS is the junior of these three flagships, offering an additional regional augmentation to even Galileo’s world-leading navigation services. Collectively, Copernicus, Galileo and EGNOS play a major role in supporting EU ambitions in other sectors, including the Common Fishery Policy (CFP), Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), the European Green Deal and Europe’s projected ‘digital transformation’.

Yet these and future successes are facing increasing challenges. In the military sphere a number of states have been adopting an increasingly militarised posture towards and in space, including through the development of new anti-satellite (ASAT) capabilities (both kinetic and not). Technologically advanced militaries such as the American and Chinese armed forces are almost entirely dependent on satellites for communications, PNT and as part of intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities. As Daniel Fiott of the EU Institute for Security Studies notes, ‘from a military perspective, disabling satellites or disrupting space-to-earth signalling and communications is a method of plunging terrestrial capabilities into “operational darkness”.’ This possibility was recently thrown into sharp relief once again when Russia carried out a kinetic ASAT test, intercepting an inactive satellite with a missile, destroying it and in the process creating over 1,500 trackable pieces of debris between 300-1,100km above the Earth’s surface (within Low Earth Orbit, LEO). Growing levels of debris threaten to turn an already busy environment into an actively dangerous one, with the theorised possibility of the ‘Kessler Syndrome’, a catastrophic cascade of collisions and break-up events leading to an unnavigable and unusable space domain, becoming more likely with every new fragment of debris discarded into space.

Even without considering debris, LEO is a cluttered environment set to become ever-more intensely busy. According to the UN’s Outer Space Objects Index, there are currently around 8000 objects currently orbiting Earth, spread across not only LEO but also MEO (Medium Earth Orbit) and GSO (Geosynchronous Orbit), of which somewhere around 3,000 are likely currently active satellites. This number is set to rise by orders of magnitude in the coming decade as private companies characterising the rise of New Space begin to deploy mega-constellations of thousands or tens of thousands of small satellites. The successful launch of just three planned mega-constellations (Starlink with 41,493 units, Guo Wang with 12,992 units and Project Kuiper with 7,774 units) would be transformative for LEO. Clearly, mega-constellations represent a step-change in human activity in space.

Other actors have started to take notice of this, with Rwanda recently having filed with the International Telecommunications Union (ITU), a global regulatory body with the mandate to authorize these constellations, for a mega-constellation of nearly 330,000 units. Feasibility aside, it is clear that actors are responding to a perceived ‘race’ for ownership of orbits in LEO (GSO, which is arguably more valuable real estate, has previously been divided equitably after international intervention). It stands to reason that LEO will have a maximum ‘carrying capacity’, increased through effective inter-actor cooperation and coordination but reduced in times of competition and suspicion. Unfortunately for Europe, geopolitical conditions among the other major spacefaring powers (the US, China, Russia) are leaning towards the latter.

Indeed, and as Fiott again notes, two major trends shape contemporary space affairs:

- Space is a geopolitical realm that is increasingly dominated by the United States, China and Russia and the fact they are increasingly investing in space for national security concerns as well as economic competitiveness.

- Space is a technological frontier and the space sector is presently subject to rapid technological shifts marked by quantum computing and communications advances, nano technologies, advanced manufacturing and robotics and Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Navigating this shifting context will require coordination of the major European space actors: the European Commission (the EU’s executive branch), the European Space Agency (ESA), the European Union Agency for the Space Programme (EUSPA) and the Directorate General for Defence Industry and Space (DG DEFIS). Despite turbulence in recent years over ESA’s relationship to the newly created EUSPA, all parties recently signed a Financial Framework Partnership Agreement (FFPA) defining their respective roles, responsibilities and mandates. The FFPA sees the European Commission act in an executive capacity as ‘project manager’, EUSPA as the ‘market-oriented’ agency focused on down-stream applications of space-based technology for industry, and ESA as the technical specialist of the three.

The FFFP, which approves almost €15bn in funding for ESA, EUSPA and DEFIS, is one of two major policy developments in the European space domain, the other being the first ever European Space Programme 2021-2027 (EUSP). The EUSP emphasises the need to ‘harness the power of space to re-ignite its post-COVID economy, address climate change, transit to digitalization, and secure its autonomy and sovereignty.’ What exactly is meant by ‘autonomy and sovereignty’ is unclear, however the language mirrors an important and high-profile debate currently at the forefront of European strategic affairs: that of ‘strategic autonomy’.

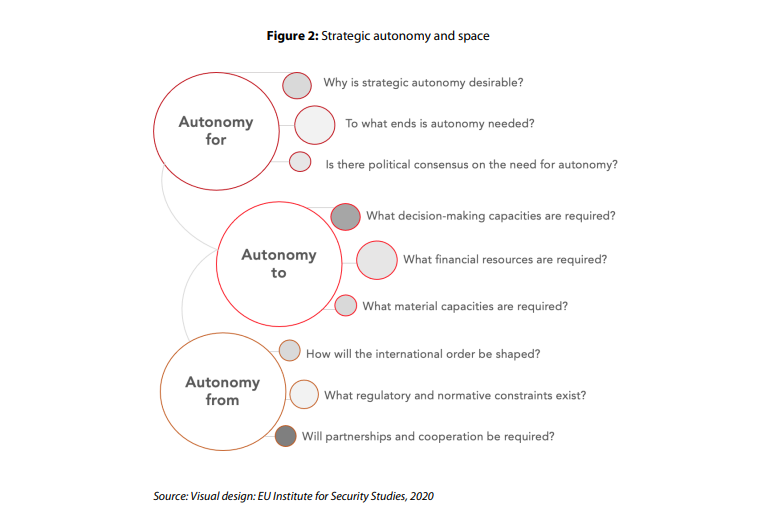

Strategic autonomy is itself highly contested, however at its most basic the concept describes the ability of an actor (here the EU) to act independently towards its own strategic goals. A better formulation can be found in Daniel Fiott’s previous quoted report ‘The European space sector as an enabler of EU strategic autonomy’, which elaborates on strategic autonomy through the lens of three types of questions: autonomy for, autonomy to, and autonomy from (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: Strategic Autonomy and Space. Source: Visual design: EU Institute for Security Studies, 2020, in Fiott, D. (2020) ‘The European space sector as an enabler of EU strategic autonomy’.

Applied to space, Fiott suggests that Europe should act to (1) enhance the EU’s autonomy in space so as to ensure the defence and economic prosperity of the EU [autonomy for]; (2) ensure that it has the political, diplomatic, financial and material resources needed to secure its strategic autonomy in space [autonomy to]; (3) lower its dependence on factors that may hinder its ability to secure its interests in space [autonomy from]. In order to achieve these goals, the report advocates for sustained, purposeful investment into space to keep the EU at the forefront of the technological frontier in space, and consequently advises the EU to debate and agree to a shared vision to guide this investment.

At the time that Fiott was writing DEFIS was still to be fully established, the EUSP was years away from coming into force, and EUSPA had not yet been created out of the previously existing European GNSS Agency. Yet despite this flurry of activity and relative increase in importance for space affairs, major challenges to developing and leveraging space for European strategic autonomy remain. In particular, analysts at the European Space Policy Institute (ESPI) highlight ‘questions related to future strategic orientations and high level governance’ which remain unanswered. Concretely, these include:

- ‘Lack of convergence in the definition of a shared long-term vision, aligning all relevant actors in terms of ambition, technological priorities, industrial policy, procurement models, roles and responsibilities,

- Different membership structure of the EU and ESA, resulting in the consequent risk of international politics interfering with space affairs,

- Risk of unnecessary duplication of efforts and dissociated parallel activities.’

While international politics certainly do present a potential complication, across the last two decades it has often been inter-organisational politics that has been a more pressing issue, most notably the at-times-strained relationship between ESA and the EU. With the signing of the new FFPA and the resultant agreement of the EU Commission’s role as the executive of European space affairs, it is perhaps not surprising that the new ESA Director General’s ‘Agenda 2025’ emphasises the need to ‘strengthen EU-ESA relations’ as the first of 5 key priorities. Recognising the Commission’s role in providing ‘important political leadership’ for European space activities (while reiterating ESA’s own position as the Space Agency of its member states), Agenda 2025 commits ESA to ‘trigger and support a political dialogue, and develop a proposal for possible evolution of the current cooperation based on a comprehensive analysis.’

The purpose and need for this political dialogue is made clear in the Agenda 2025’s executive summary: ‘First, Europe needs to reach a common understanding of where it boldly wants its space sector to go. This will be done through a political process and strong stakeholder interaction, including the development of a common European industrial policy.’ A potential mechanism for this dialogue is also described: a dedicated ‘European Space Summit’ coordinated by ESA and hosted by France as part of the EU’s ‘Conference on the Future of Europe’ in 2022.

It is unclear whether or not the Summit is currently intended to go ahead as planned in Spring 2022, however, even if delayed, such an event could be invaluable in leveraging the momentum generated by the FFPA, EUSP and Agenda 2025 to catalyse the creation of a ‘whole of Europe’ vision for space. On the agenda for discussion must surely be security, safety and sustainability in space, with building political consensus around an ASAT test ban, increased funding for active orbital debris technologies and on-orbit servicing being key steps Europe could choose to pursue. In the economic sphere, taking advantage of a rapidly widening pool of private actors keen to accelerate innovation, ensuring the long-term availability of and equitable access to LEO, and leveraging opportunities for downstream applications to support both the transition to a sustainable and digital Europe will all be important.

The current context demands proactive, thoughtful and purposeful action across multiple well-coordinated organisations, all working towards a shared vision of Europe’s future in the space domain.

Image: a model of a Galileo satellite (source: Matti Blume/CC BY-SA 4.0)

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research