July 25th, 2016

By Sarah De Geest – Junior Fellow

Peter G. Cornett – Postgraduate Fellow, Royal Geographical Society

The Need for European Participation in Freedom of Navigation in the wake of the South China Sea ruling

It is hard to live in the shadow of a giant. China’s neighbours fear more and more that its “peaceful rise” carries with it the risk of armed conflict. The increasing friction between the Asian giant and its neighbors—as they each seek to maintain territorial sovereignty—makes the Asia-Pacific one of the most precarious flashpoints on earth. Seemingly intent on expanding its influence irrespective of international norms and legal restrictions, Chinese policy in the Asia-Pacific has become a regular concern for EU and US policy makers. The recent verdict by International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea has intensified China’s response. It called the court a “puppet” of external forces and considers setting up an air defense zone over the South China Sea.[1]

To visibly demonstrate its displeasure at Chinese behavior ranging from territorial aggrandizement to Anti-Access Area Denial (A2/AD) and attempts to establish regional Air Defense Identification Zones (ADIZ) in strategic waterways, the United States (US) has stepped forward uphold international law through the exercise of freedom of navigation operations (FONOP), sailing vessels and flying planes in and around the South China Sea. The conviction of the US is that the exercise of FONOPs are required in order to prevent Chinese dominance of the South China Sea. Other liberal powers such as the EU, the United Kingdom, and Australia also have an interest in upholding freedom of navigation since the liberal rules-based order benefits their growth and security. Nevertheless, thus far, FONOP operations in the South China Sea have been carried out almost exclusively by the US. As the primary guarantor and enforcer of the liberal international order, the US provides leadership on enforcing freedom of navigation, but in so doing it cannot be expected to act alone, particularly against two Eurasian great powers (Russia and China) simultaneously. Met with a deafening silence from liberal powers after attempting to raise coalitional support for FONOPs and against Chinese aggrandizement, the contemporary world order and its liberal features rest precariously on the shoulders of an Atlas who—due to domestic pressures and a lack of international support—appears increasingly inclined to shrug.

Despite their relative lack of substantive action concerning Chinese aggrandizement in the South China Sea, European powers recognize the importance of these strategic waterways. The new European global strategy document proclaims that the EU seeks to become a “global maritime security provider” that will “seek to universalize and implement the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, including its dispute settlement mechanisms.”[2] It highlights the EU’s interest in “open and protected ocean and sea routes critical for trade and access to natural resources,” and further states that its “prosperity hinges on an open and rules-based economic system…”[3]

In light of the EU’s stated interests in freedom of navigation, we seek to explore the EU’s policy options in contributing to the reinforcement of this legal principle.

Chinese maritime disputes and freedom of navigation

Maritime freedom of navigation is an essential principle of the liberal international order. Born from mare liberum—the 17th century legal concept of the freedom of the seas—and strengthened by contemporary international law as enshrined in the 1994 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). It has been a longstanding principle that all nations have the right to navigate international waters without restraint. This right directly enables and ensures the freedom of international trade since an estimated 90% of world trade is transported by sea.[4]

In recent years, China’s grand strategy appears driven by a bid to extend its soft power on the Eurasian continent while simultaneously taking a more aggressive approach as it pursues military expansionism in the maritime domain.[5] In the South China Sea in particular, it continues its activities, ranging from the creation and militarization of artificial islands to the extension of its grasp to include the Paracels and Spratley Islands and Scarborough Shoal.[6]

Arbitrary in nature, China’s ‘historic interpretation’ of its sovereign territory leaves little room for its neighbors.[7]

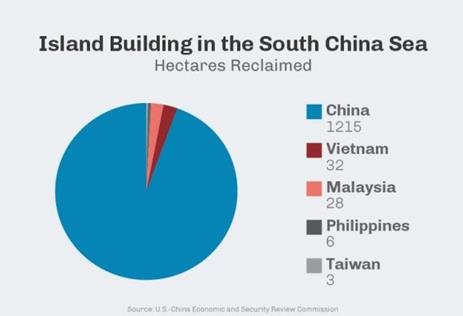

On the Chinese side, some argue that China is merely reacting to provocation. For example, as Xue Li claims, China’s behavior compares to that of Vietnam, Malaysia, Taiwan, and the Philippines and differs only in quantity, not quality.[8] This comparison overlooks the perceived character of the building and militarization of artificial islands, the 9-dash line policy, and the establishment of A2AD/ADIZ outside of territorial waters.[9] While China has no qualms placing missile systems on the Paracels or building airstrips in the Spratley’s—despite ‘recognizing’ the existence of disputes over the Spratly Islands—it continuously claims that it wishes to solve these issues through negotiation.[10] However, one does not exclude the other, as the ITLOS verdict (in the absence of Chinese participation) merely provides the Philippines with an internationally recognized set of facts it can take forward into future negotiations. Though China claims it is being rushed into a decision, these issues have been ongoing since 2002 when China and the ASEAN nations signed a Declaration of Conduct.[11] Additionally, the stance taken by ASEAN countries on China’s military expansionism and aggressive rhetoric shows that they have little faith in China’s willingness to reach an agreeable solution for all parties involved.[12]

As is evident from the enclosed map[13], China is not content with the legal boundaries that are attributed to UNCLOS. Shicun Wu, president of China’s National Institute for South China Sea studies, confirms that the Chinese government considers the expansive 1947 nine-dash line the real status quo and part of China’s legitimate sovereign territory.[14] China’s position on this issue—often cited as a blatant disregard for international law—has potential consequences for the future of liberal international norms and freedom of navigation.

If China were to follow the example of other illiberal powers and threaten to close off or restrict access to its surrounding waters, it would at the very least do grave damage to maritime trade in the region.[15] For example, Iran has on numerous occasions threatened to close off the Gulf to the US and its allies, and this has been cause for worry among states that import oil that traverses through the Strait of Hormuz. Many see China’s ADIZ and A2/AD practices as demonstrative of China’s willingness to acquire the means to back up such as threat.[16]

It may be prudent to ask if a provocateur can be identified. In order to do so, it is helpful to look at the case of Indonesia—the largest of the Southeast Asian countries—which has been extremely patient as Chinese fishing vessels crowd its territorial waters. While countries such as the Philippines and Vietnam are becoming more assertive in voicing their concerns with Chinese expansionism, up until recently Indonesia has remained neutral. Like with many other countries in the region, Indonesia’s economy is in need of Chinese investment. But, China also needs them, and in order to keep the balance it is necessary to provide a proper economic climate of freedom and open trade. Ensuring the continuation of these principles is very much in the interest of the EU.

The importance of FONOP to the liberal international order

For rules to be meaningful, they must also be enforceable and as is the case with all international law, UNCLOS and the principle of freedom of navigation have an enforceability problem; international legal principles lack an ultimate enforcement mechanism. Outside of the restraints that powerful states agree to place upon themselves and each other, the only enforcers of international law are coalitions of other powerful states. Importantly, states that carry out FONOPs assert rights on behalf of all nations to freely navigate international waters. As the US Assistant Secretary of State for East Asia and the Pacific has stated at a May 2015 news conference in Hanoi, “if the world’s most powerful navy cannot sail where international law permits… what about the fishermen, what about the cargo ships? How will they prevent themselves from being blocked by stronger nations?”[17]

The Chinese government loudly condemns US FONOPs, asserting that these operations constitute “political and military provocations against China” that are “very dangerous” because they could “easily lead to unexpected incidents.”[18] Despite the claims of Chinese propagandists, these operations exercise and reinforce legal rights while providing a much-needed counterbalance to China’s excessive maritime claims in one of the world’s busiest strategic waterways.

Strategic interests in FONOPs and open sea-lanes are manifold, but two are relevant to this argument. First, keeping sea-lanes open for maritime trade is essential to Europe, the US and global trade more generally. For instance, as Robert Kaplan observes, 2/3 of South Korean and 60% of Japan and Taiwan’s energy supplies travel through the South China Sea.[19] If China came to dominate the region, the energy security of those who oppose it could be placed at risk. In addition to risks to the import of strategic resources, the South China Sea is itself home to more than (much more, by some estimates) 7 billion barrels of oil and 900 trillion cubic feet of natural gas.[20] Moreover, an enormous portion of global trade—more than $5 trillion—traverses the South China Sea each year. Similarly, as ASEAN is set to become the fourth largest economy by 2050, the EU’s economic interests stem from its stake in trade, financial, political and societal interconnections with countries in the region, leaving little doubt that any conflict would significantly affect EU interests.[21] Moreover, in recent years the EU has been intensifying contacts with ASEAN and calling for a strategic partnership with the region.[22] Summits and high-level dialogues could strengthen this effort by ensuring diplomatic progress, stability, and to convey the seriousness of Europe’s commitment to its new partners.

A second strategic interest in maintaining freedom of navigation concerns the Eurasian balance of power. To contain the Soviet Union and ensure the Eurasian balance of power during the Cold War, the US and its allies leveraged control of strategic waterways to place geostrategic pressure on the Soviet Union, often in regions far from European territory. While European powers do not share the same military alliances as the US in Asia, they share a strategic interest in maintaining the continental balance of power and in ensuring unimpeded maritime trade and freedom of navigation. As many key European states are also maritime great powers, maintaining access and presence in the maritime domain is essential for both warfighting and power projection.

European geostrategy and FONOP

Some may argue that Europe has no immediate interest in joining US FONOPs in support of liberal international norms, but this perspective tends to ignore the wider geopolitical context and burgeoning trade relations in the region. Shifts in the Eurasian balance of power and threats to transit routes will have strategic effects on every country in the EU, and due to the nature of 21st century trade and navigation, whether these developments emerge from NATO’s eastern flank or Japan’s western flank is largely irrelevant. Outside of concerns related to upholding international law and the liberal international order, the EU has self-interested geostrategic reasons to oppose maritime aggrandizement by rising powers.

Recently, the European Commission advanced a policy document that expresses concern at Chinese behavior in the South China Sea.[23] Although it still must be approved by member states, the document argues that “the large volume of international maritime trade passing through that area means that freedom of navigation and over flight are of prime importance to the EU.”[24] Further, the paper suggests that “the EU should encourage China to contribute constructively to regional stability… and support for the rules-based international order.”[25] Despite US requests that the EU explicitly reject China’s expansive claims, the EU remains largely neutral on South China Sea territorial disputes.[26] Similar in tone to EU texts, the UK’s 2015 national strategy document celebrates the UK’s historical role in shaping the contemporary liberal international order, including norms such as freedom of navigation.[27]

Ostensibly aware of the recent fragility of the liberal world order and principles such as freedom of navigation, the French have been the first to openly suggest contributing to South China Sea FONOPs. Speaking at a security conference in Singapore, French Defense Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian called for a “regular and visible” European naval presence in the South China Sea.[28] “If we want to contain the risk of conflict,” he argued, “we must defend this right and defend it ourselves.”[29]

Rightly citing the system consequences of allowing China to quash the freedom of the seas, Le Drian explained, “if the law of the sea is not respected today in the China seas, it will be threatened tomorrow in the Arctic, in the Mediterranean, or elsewhere.”[30] More than a simple declaration of values, the view of French defense officials seems to be that freedom of navigation in the South China Sea is not a theoretical issue but an actionable area of concern. Other European nations should seriously consider following the French example and seek to actively deploy military assets in support of US FONOP.

Policy options and recommendations

The continuation of an international order based on the rule of law, free trade, and liberal values remains a core strategic goal of EU policy. As liberal democracies with an interest in maintaining a liberal international order, European states must begin to take substantive action in support of US efforts to uphold maritime freedom of navigation, shouldering the burden of protecting liberal economic and security interests alongside the US. Regular and visible FONOPs in the South China, in cooperation with US or as voluntary cooperation between EU states (for example the UK and France, with or without the US), could provide a much needed united front in defense of freedom of navigation and the liberal international order. Policymakers should therefore consider these options:

- The EU could continue to take a passive role and adopt a ‘wait-and-see’ posture. This would probably result in better relations with China in the short term. On the other hand, whatever role the EU wishes to take with respect to freedom of navigation, it seems rather unlikely that China would risk its potentially lucrative economic relations with the EU, as positive China-EU relations are increasingly necessary as China pursues its ambitious “One Belt, One Road” policy. If this approach is adopted, the EU should above all be careful not to let the Chinese lobby pressure its interest and value system.[31]

- Rather than becoming directly involved in FONOPs, as long-time supporters of a Code of Conduct in the South China Sea, EU policymakers could continue to voice support for international legal norms on freedom of navigation, including regular and public declarations of support for US FONOP efforts in the Asia-Pacific. In this approach, when states take actions that threaten freedom of navigation, such as the declaration of ADIZ or the deployment of A2/AD in support of a territorial claim, EU policymakers and heads of state should be swift to publicly condemn these actions, voicing support for liberal norms and efforts to uphold them. Summits and high-level dialogues could strengthen recent efforts to highlight Europe’s commitment to ASEAN and partners in the region.

- European nations could take an active role by joining US FONOPs or undertaking independent operations in the South China Sea. For example, countries with specific interest in the region like France and the UK could engage in joint FONOPs, either by themselves and/or together with the US and other liberal Asia-Pacific powers, such as Australia, India, and Japan.

If a European consensus could not be obtained for the active involvement in FONOPs, a hedging approach would be ideal, as it would allow the EU to tailor its policy response to changes in Chinese behavior. Should Chinese policy in the region shift further towards belligerence, the EU would retain the option of escalating its involvement in the region. Such an approach is consistent with European strategic interest in counterbalancing risks to maritime access and the liberal international order. It would also ensure the EU’s flexibility in reacting to changes to China’s domestic politics, which is currently riding a trend towards extreme nationalism.[32]

Considering Russia’s revanchism in Crimea and the ongoing disputes in the East China Sea and the South China Sea, it should be clear to Europeans that liberal values do not enforce themselves, and while eastern Eurasia and the South China Sea may seem geographically distant, there is no reason to expect that tensions will remain confined to the region. Moreover, with its tremendous growth potential, Asian states are fast becoming important European partners; security and a liberal peace are essential to further improve trade ties and diplomatic relations. It is equally important to note that FONOPs are not a panacea, but rather should be conceptualized as an essential element of a proactive and comprehensive strategy for upholding the contemporary liberal international order. If Europe does not wish to witness the continued fracturing of this order and its related norms, it should consider taking some action, not just close to European shores, but also on a global scale.

For its part, China regularly proclaims its intentions to reshape the international order in its own image through cultural and economic foreign policies.[33] While more exchanges between Europe and Asia will remain important and should be encouraged to increase mutual understanding and cooperation, Europe should be attentive to the problems that come with the China’s increasing authoritarian stance.[34] As such, it is crucial that European states continue to champion liberal norms as a primary goal of their foreign policies.[35] Additionally, Chinese actions carry the risk of emboldening states like Russia to expand their spheres of influence through similar means. Russia has already witnessed a decade of European neglect in the South China Sea, and what it has learned from successful Chinese actions in the Asia-Pacific, it is now applying in the Black Sea.[36]

International legal norms such as freedom of navigation and other liberal principles must be actively upheld for them to remain relevant, and not solely by the United States. In the words of Michael Howard, “Throughout human history mankind has been divided between those who believe that peace must be preserved, and those who believe that it must be attained.”[37]

Download as PDF.

[1]China vows to protect South China Sea sovereignty, 14 July 2016, [Link].

[2] EU Global Strategy, 28 June 2016, p.41, [Link].

[3] Ibid, p. 41.

[4] International Chamber of Shipping [Link]; International Maritime Organization [Link].

[5] P.G. Cornett, China’s “New Silk Road” and US-Japan Alliance Geostrategy: Challenges and Opportunities, June 2016, [Link].

[6]At Scarborough Shoal, China Is Playing With Fire: Retired Admiral, 16 June 2016, [Link].

[7] Map used in a 2015 article by the BBC, [Link]; The Lowy Institute provides a more detailed map of conflicting maritime claims at [Link].

[8] Every country in the region is engaged in some form of land reclamation, Xue Li Interview, [Link]; Graph:“Island Building in the South China Sea”, [Link].

[9] Ibid

[10] Xue Li Interview, [Link];.

[11] Declaration of Conduct South China Sea, [Link].

[12] The truth behind ASEAN’s vanishing South China Sea statement, [Link].

[13] Map used in a 2015 article by the BBC, [Link]; The Lowy Institute provides a more detailed map of conflicting maritime claims. [Link]

[14] Fu Ying, Wu Shicun, South China Sea: How We Got to This Stage, 9 May 2016 [Link].

[15] Iran and the threat to close the Gulf, see examples [Link], [Link]; China: An Illiberal, Non-Western State in a Western-Centric, Liberal Order?, 2014, [Link].

[16] Who will stand against China this year?, 12 March 2016, [Link].

[17] US: Yes, China, we did sail a warship near a disputed reef in the South China Sea, 10 March 2016, [Link].

[18] US ‘freedom of navigation’ operations in South China Sea ‘very dangerous’: China, 28 April 2014, [Link].

[19] Robert Kaplan, Asia’s Cauldron, 2014, Kindle, loc. 225.

[20] Ibid.

[21] EC and EP joint communique on EU and ASEAN [Link]; Europe’s potential in addressing maritime security in Asia: a Japanese view, 29 June 2016, [http://www.epc.eu/pub_details.php?cat_id=4&pub_id=6768&year=2016Link]; South China Sea disputes, what is in it for Europe, 15 June 2014, [Link].

[22] EU Eyes Strategic Partnership With ASEAN as New Mission Officially Opens, 28 January 2016, [Link].

[23] EU calls for free passage through South China Sea , 22 June 2016, [Link].

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid.

[27] UK National Security Strategy and Strategic Defence and Security Review 2015 [Link].

[28] Europeans Push Back Against Beijing in the South China Sea, 6 June 2016, [Link].

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31]“China uses its leverage and lobbies the European Union to stay out of the South China Sea dispute. As a result the European Union tries to avoid this issue, leaving the United States to fight on its own for freedom of navigation there”, Theresa Fallon, Is the EU on the Same Page as the United States on China?,

30 June 2016 [Link]

[32] East, west, home’s best, 9 June 2016, [Link].

[33] Ibid; China’s emerging vision for world order, May 2015 [Link]; see examples: Confucian Institutes [Link] and [Link]; OBOR [Link].

[34] Experts point to the worrisome trend and renewed crackdown on activists, human rights lawyers and political dissidents since President Xi Jinping took power in 2012 [Link] and EP’s Freedom of Religion and Belief Report 2016 [Link].

[35] For example, see China’s ‘new type of Great Power relations’: a G2 with Chinese characteristics?, Chatham House, July 2016 [Link].

[36] Memo to NATO: Wake Up Before Putin Turns the Black Sea into a Russian Lake, 28 June 2016 [Link].

[37] Michael Howard, The Invention of Peace: Reflections on War and International Order, 2000, p.6.

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research