By Carolina Rocha da Silva, Research Assistant – Human Security Centre

16th September 2014, Human Rights and Conflict Resolution, Issue 3, No. 6

In the past month, two American journalists, James Foley and Steven Sotloff, and one British aid worker, David Haines, were beheaded by the Islamic State (IS), bringing to the public fore the question of kidnapping for ransom (KFR). Terror-related KFR is a worrying, growing and increasingly violent trend that raises a difficult dilemma to governments: should states, businesses and families comply with terrorist groups in order to save the lives of the kidnapped, or should these men be left behind in order to fight against terrorism? What remains certain is that the payment of ransom will continue to help financially and ideologically sustain terror groups.

Kidnapping by terrorist groups: a growing, more violent and more religious trend

Complete and precise information on kidnapping is scarce and nearly impossible to verify due to the nature of the activity and to how the victims and governments, families or businesses respond to it. James Forest estimates that 80% of all kidnap for ransom go unreported [i], but some trends can still be identified. Kidnapping incidents represent only a small minority – 6.9% – of all terrorist attacks each year. However, in parallel with the increase of terrorist incidents per year, kidnapping by terrorist groups had also risen over the last 40 years, as can be observed in figure 1.[ii]

Figure 1. Kidnapping incidents recorded in GTD, 1970-2010.[iii]

Most of these terror-related kidnapping incidents have occurred in a small number of countries such as Colombia (18.2%), India (8.3%), Pakistan (6.3%), the Philippines (6.2%), Iraq (5.0%) and Afghanistan (4.6%).[iv] Until the late 1990s-early 2000s the epicentre of KFR was South America, with Colombia leading. Interestingly, due to the success of the Colombian fight against terrorist and because of the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan this trend has shifted in the past years. As apparent in figure 2, 3 and 4, the proportion of terror-related kidnapping incidents in South America have exponentially declined, being replaced by increasing KFR occurrences in the Middle East and South Asia.

Figure 2. Proportion of all incidents and kidnapping incidents in South America.[v]

Figure 3. Proportion of all incidents and kidnapping incidents in the Middle East.[vi]

Figure 4. Proportion of all incidents and kidnapping incidents in South Asia.[vii]

This geographical shift is also mirrored in the activity of terrorist groups. For the past 40 years, the top ten groups responsible for KFR incidents have been firstly the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), secondly the National Liberation Army of Colombia (ELN), thirdly the Taliban and fourthly the Communist Party of India – Maoist (CPI-M).[viii] However, since 2006 the Taliban have led the world in terror-related kidnapping incidents[ix], solidifying the link between KFR and Muslim extremist groups. Today, not only the Taliban but also the Al Qaeda and its affiliates, the Al Qaeda in the Lands of the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and the Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), and the Islamic State (IS) frequently recur to kidnapping for ransom. Westerners have been the most frequent foreign targets for terrorists, but there are significant country-level variations: in India, Afghanistan, Colombia and The Philippines, US citizens have been the number one foreign abductees; in Pakistan, the majority of victims consists of Afghanis; and in Iraq and Nigeria, the British are the most abducted.[x]

Kidnapping: a terror strategy

Terror-related kidnapping serves significant political goals, as it is a fairly simple method of gathering public attention, of communicating political positions and of obtaining concessions that would not materialize otherwise. Kidnapping incidents create a climate of fear both nationally or internationally, as terrorist attacks do. Locally, kidnapping forces the obedience of local communities, as occurred in Iraq with Al Qaeda and in Nigeria with Boko Harem. In Northern Ireland, the Provisional Irish Republic Army would capture individuals that were suspected of collaboration with the authorities in order to coerce the behaviour of the community.[xi] Internationally, terror-related kidnappings are used to communicate political stances. For example, the IS makes its abductees wear an orange jumpsuit in protest against the holding of prisoners in Guantanamo Bay, and argues that Foley’s execution was in retaliation for the recent airstrikes against the group in Iraq.[xii] The beheading of David Haines was also presented as a reaction to the recent international coalition to fight against the IS.[xiii] Moreover, terror-related kidnappings are also a form of obtaining concessions from foreign governments. For the Hamas, ‘the kidnapping is not an end; it is a means for the release of all our prisoners’, said the group’s spokesman.[xiv] Indeed, Israel has already freed several jailed militants in exchange of kidnapped Israelis or bodies of dead citizens. Also, the IS has demanded the liberation of convicted terrorists such as Aafia Siffiqui, an M.I.T.-trained Pakistani neuroscientist with ties to Al Qaeda currently incarcerated in Texas.[xv] Therefore, kidnappings fulfil significant political goals.

Kidnapping: a war economy

For terrorist groups, kidnappings are also an extremely important self-funding method. As any other insurgent armed group, terrorists sustain themselves via ‘war economies’, characterized by Ballentine and Sherman as parasitic, rent-seeking, short-term and predatory methods like drug trafficking and kidnapping for ransom.[xvi] Kidnapping for ransom, or the taking of individuals as hostages while demanding that their governments, employers or families pay huge sums of money for their release, is an extremely successful money-generating scheme. Every transaction encourages a new one, creating a vicious cycle of kidnapping for ransom. The money gathered is used by the terrorists to held fund their activities including recruiting and indoctrinating new members, paying salaries, establishing training camps, acquiring weapons and communications gear, organizing attacks and helping support the next generation of extremist groups.[xvii]

An investigation by the New York Times found that Al Qaeda and its affiliates, the AQIM and the AQAP, have gathered at least $125 million from kidnapping for ransom since 2008.[xviii] Kidnapping Westerners has become the main source of revenue for Al Qaeda and its affiliates, strengthening their influence in the world. “Kidnapping hostages is an easy spoil […] which I may describe as a profitable trade and a precious treasure”, wrote Nasser al Wuhayshi, the leader of AQAP.[xix] Recently freed IS prisoners said that their captors were well aware of what ransoms had been paid to Al Qaeda and were hoping to abide by the same business plan. Indeed, the group had demanded a $132 million ransom for James Foley’s release, according to Philip Balboni, the chief executive and co-founder of Global Post, where the journalist worked.[xx]

Worryingly, KFR appears to be an increasing trend. The number of incidents has been increasing, as shown in figure 1, with about 50 abducted foreigners in the past five years.[xxi] Additionally, the size of the average ransom per hostage is rising. In 2010 the AQIM would demand about $4.5 million per abductee and only a year later the amount increased to $5.4 million.[xxii] Of the $125 million Al Qaeda gathered since 2008, $66 million were paid out in 2013.[xxiii] The urge to stop the kidnapping for ransom cycle is pressing.

The international community and KFR: a torn response

The kidnapping for ransom cycle is perpetuated because of the dilemma it poses. Not to pay ransoms is to jeopardize innocent lives, as just happened with Foley, Sotloff and Haines. For this reason, European countries directly pay ransoms to terrorist groups, except the United Kingdom. Since 2008, France has given $58.1 million, Switzerland $12.4 million, Spain $11 million and Austria $3.2 million.[xxiv] However, there is another side to the story: paying ransoms means helping sustain terrorist groups that are dedicated to taking many other innocent lives. Firstly, as every ransom paid leads to another abduction, the cycle is perpetuated. Secondly, the insurgents are left stronger, empowered and more able to organize large-scale attacks. ‘Europe has become an inadvertent underwriter of Al Qaeda’, as the New York Times puts it.[xxv]

In 2001 the United Nations adopted an anti-terrorism resolution that requires states not to pay kidnap ransoms, but without creating legal obligations to do so. ‘It is […] imperative that we take steps to ensure that kidnap for ransom is no longer perceived as a lucrative business model and that we eliminate it as a source of terrorist financing’, said the British UN Ambassador Mark Lyall Grant.[xxvi] Therefore, the US and the UK neither pay ransoms nor negotiate with terrorist groups. Moreover, the US does not let private companies paying ransoms to terrorists.[xxvii]

The disparate Western response motivates the perpetuation of both European and American kidnapping. However, while the formers are saved, the latters are not: this spring, four French and two Spanish citizens were saved while Foley, Sotloff and Haines died. A fourth detainee is now being threatened. Hostage takers tend to prefer not to kidnap American or British citizens[xxviii] who do not pay, but this was not enough to save the journalists’ lives argues David Rhode, a Pulitzer-winning journalist who had been kidnapped by the Taliban. Additionally, complying with captors provides a continuous flow of revenue for terrorist groups. Rhode sees as the only solution for KFR a common Western policy of non-payment and non-negotiation. This is an extremely difficult position, but saving one individual might do harm to many more. In the words of Michael Ignatieff, non-compliance with abductors is a ‘lesser evil’.[xxix]

Fighting against KFR: prevention, refusal and denial.

The UN, US and UK policy against terror-related kidnapping seems to be the only option to break the KFR cycle, but it should not be limited to the denial of negotiations with the captors. The first step to limit kidnapping incidents is prevention. As the US Under Secretary for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence puts it, there is no better strategy to counter KFR than to keep the potential victims out of harm’s way.[xxx] Already more than 160 countries cooperate in the prevention of hostage-taking under the 1979 International Convention against the Taking of Hostages. Prevention tactics towards Somali piracy incidents such as increasing speed near suspicious vessels and being outfitted with razor wire or high-pressure sprays have already helped decrease about 50% of occurrences.[xxxi] In the case of kidnapping, then the response should be two-fold: Western government should refuse to make concessions to terrorist in order to prevent them from benefitting from their crimes, while resorting to forceful actions such as rescue operations. In spite of their limited success, these methods decrease the profits of kidnapping and increase its risks.

A common international response to KFR: enough to curtail the kidnapping cycle?

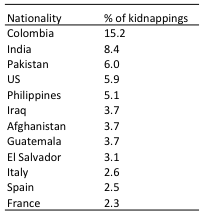

KFR is one of the most lucrative sources of revenue for terror-related insurgents, thus limiting the kidnapping of foreigners is crucial to break the cycle. However, it is not enough. As Forest discusses, the majority of the abductees are locals, citizens from the countries where they are abducted. This contrasts with the good deal of media coverage focusing of kidnapping of foreigners. Kidnapping middle class locals and demanding ransoms from their families seems less risky than kidnapping foreigners and negotiating their release with foreign governments or businesses. A strong correlation is apparent between the top twelve nationalities among victims of terror-related KFR listed in table 1 and the countries with higher kidnapping percentages: Colombia, India, Pakistan, the Philippines, Iraq and Afghanistan. Foreigners tend to account less than 10% of victims globally.[xxxii]

Table 1. Top nationalities among victims of terror-related kidnapping incidents, 1970-2010.[xxxiii]

Therefore, if kidnapping foreigners becomes less lucrative, terrorists will increase their efforts towards locals. For this reason, the UN and the Western governments engaged in the anti-KFR fight have to work multilaterally with the most vulnerable governments. Preventing, refusing and denying policies also need to be enforced at the micro and macro level in countries like Colombia, India, Pakistan, Iraq, Afghanistan, amongst others. At the micro-level, the protection of local citizens should be enforced and families should refuse to make any concessions to kidnappers. At the macro-level, the governments need to develop a regulatory framework and operational capacities to fight against money laundering, terrorist financing regimes and kidnapping operations per se. According to Cohen, the US has started supporting vulnerable governments.[xxxiv]

Anti-KFR policies: moral dilemmas with no easy solutions

Kidnapping for ransom poses on of the most difficult dilemmas for a government: to save an individuals’ life while jeopardizing the future security of its population or to let the individual die while preventing harm to many others. The ‘lesser evil’ option is the latter. However, following this path is extremely hard not only due to the dilemma it poses but also because it has to be a worldwide coordinated policy. As it is becoming obvious these days, it is simply impossible for just two western governments to enforce anti-KFR policies alone. Europe and the US, where significant victims of kidnapping come from, need to stand together in non-compliance with terrorist groups. However, local governments such as the Colombian, the Indian, the Pakistani and the Afghani need to coordinate their responses to kidnapping for ransom. Otherwise, the KFR cycle will continuously be sustained.

Carolina Rocha da Silva is a Research Assistant with the Human Security Centre. Contactable at: carolina.dasilva@hscentre.org

Please cite this article as:

Rocha da Silva, C. (2014). ‘Responding to terror-related kidnapping: a torn Western reaction’. Human Security Centre [Group Name], Issue 3, No. 6.

[i] J. Forest, ‘Global trends in kidnapping by terrorista groups’ Global Change, Peace and Security, 2012, p.312.

[ii] Ibid., p.314.

[iii] Ibid., p.314.

[iv] Ibid., p.314.

[v] Ibid., p.317.

[vi] Ibid., p.317.

[vii] Ibid., p.317.

[viii] Ibid., p.318.

[ix] Ibid.p.319.

[x] Ibid., p.321.

[xi] Ibid., p.322.

[xii] R. Callimachi, The New Work Times, 20 August 2014.

[xiii] R. Callimachi, The New York Times, 13 September 2014.

[xiv] M. Levitt, ‘Hamas’ Not-so-secret weapon’, Foreign Affairs, 2014

[xv] R. Callimachi, The New Work Times, 20 August 2014.

[xvi] K. Ballentine, J. Sherman, The Political Economy of Armed Conflict: Beyond Greed and Grievance, Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2003.

[xvii] D. Cohen, ‘Kidnapping for Ransom: The Growing Terrorist Financing Challenge’, Chatham House, 2012.

[xviii] R. Callimachi, The New Work Times, 29 July 2014.

[xix] Ibid.

[xx] Ibid.

[xxi] Ibid.

[xxii] D. Cohen, ‘Kidnapping for Ransom: The Growing Terrorist Financing Challenge’, Chatham House, 2012.

[xxiii] R. Callimachi, The New Work Times, 29 July 2014.

[xxiv] ‘Ransom Payments to Al Qaeda in 2013’, Havocscope – Global Black Market Information.

[xxv] R. Callimachi, The New Work Times, 29 July 2014.

[xxvi] M. Nichols, ‘U.N. Security Council urges end to ransom payments to extremists’, Reuters, 27 January 2014.

[xxvii] K. Gander, ‘ISIS hostage threat: Which countries pay ransoms to release their citizens?’, The Independent, 3 September 2014.

[xxviii] Ibid.

[xxix] M. Ignatieff, The Lesser Evil, Political Ethics in an Age of Terror, Edinburgh University Press, 2005, pp.1-24.

[xxx] D. Cohen, ‘Kidnapping for Ransom: The Growing Terrorist Financing Challenge’, Chatham House, 2012.

[xxxi] Ibid.

[xxxii]J. Forest, ‘Global trends in kidnapping by terrorista groups’ Global Change, Peace and Security, 2012, p. 320.

[xxxiii]Ibid., p.320.

[xxxiv] D. Cohen, ‘Kidnapping for Ransom: The Growing Terrorist Financing Challenge’, Chatham House, 2012.

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research