26 October, 2022

by Sam Biden, Research Assistant

The Veil in Iran

Since the Iranian-Islamic revolution in 1979, compulsory veiling has plagued the lives of Iranian women. Immediately after the revolution, newly sworn-in leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, began to declare that veiling was to become a mandatory part of life in Iran. Shortly after this announcement, legislation was passed which would replace the prior Iranian penal code with the Islamic penal code of the Islamic Republic of Iran. This penal code is split into ‘Books’ and Articles, with Article 638 of Book #5 being of significant importance. This Article allows the Iranian parliament to enforce violent punishments for failing to wear the veil, including 74 lashes for women showing their hair and up to 60 days imprisonment.

Khomeini insisted that the women involved in the revolution were those who wore ‘modest clothing’. He went on to attack women who failed to adhere to a strict set of Islamic-expressive rules, stating:

“These coquettish women, who wear makeup and put their necks, hair and bodies on display in the streets, did not fight the Shah. They have done nothing righteous. They do not know how to be useful, neither to society, nor politically or vocationally (sic). And the reason is because they distract and anger people by exposing themselves.”

These attacks on freedom of religious expression did not fall upon deaf ears among those targeted, many female lawyers, students and workers gathered to discuss their rights, claiming the revolution took a ‘step backwards’. A new societal norm branding non-veiling women as ‘Western whores’ who were subjected to the influence of Western, liberal concepts emerged rapidly. The developing and opposing view of compulsory veiling was at odds with what Khomeini saw as an imposition of Western, emancipated women in his newly reformed nation. One assessment is such that the wearing of the veil provides for a private sphere involving the patriarchal protection of women in an attempt to ‘take back familial honour’ and create a cultural hegemony in favour of Islamic interpretations.

Initial Protests

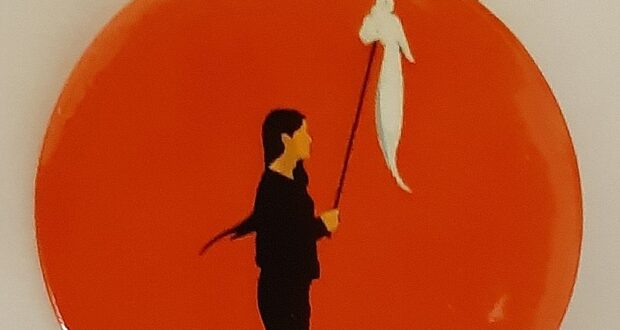

Vida Movahed is an Iranian woman who was convicted under the compulsory veiling laws in 2017. She removed her hijab before fashioning it to a pole on the populated Tehran street. Movahed was motivated by the online campaign ‘My Stealthy Freedom’ started by Masih Alinejad, an Iranian-American journalist. The online campaign was born when Movahed was overwhelmed by photos from female, Iranian readers that showed them being forced to wear the veil in response to Movahed posting a picture of her without wearing a veil. The campaign has vast exposure within Iran with a predicted 5.6m followers from inside the country.

Movahed’s actions would inspire many other women to follow suit. The newly spawned protests under the informal banner of the ‘Girls of Enghelab’ would occur in waves from 2017-2019, resulting in over 30 arrests with some women being jailed for 2 years. These sentences are atypical as the legislation provides for a maximum of either a fine or two months imprisonment, yet many of these women were given between 1-10 years in prison.

February 2018 saw the largest interventions by the Iranian government. On February 1, the Iranian police announced they had arrested 29 women for taking off their hijab. The next day, Narges Hosseini, an Iranian lawyer was charged with ‘sinful’ acts, yet was released on temporary bail on February 17. Between February 21-24, 3 women were violently ejected from protests by Iranian police for similar acts. Shaparak Shajarizadeh was the first to be arrested after being attacked from behind by Iranian police. She was fashioning the white scarf, a symbol of rebellion against compulsory veiling. She reports being beaten by police for her beliefs while in custody yet was released safely on temporary bail. Maryam Shariatmadari was the next target of the Iranian police. When questioned as to what she was protesting against, she refused to answer. Iranian police violently removed her from the street and she suffered a broken leg due to the unlawful force used. 2 days later, Hamraz Sadeghi was given similar treatment, suffering a broken arm at the hands of an ‘unidentified’ security force.

Crackdowns and Consequences

The Iranian government would begin to crack down on many aspects of both social life and political expression. Leisure areas were targeted by the State Security Forces (SSF) in the Summer of 2020 in an attempt to repress any women from violating veiling laws. Additionally, 194 new patrol teams were allocated to beaches in Northern Iran to bolster a new social crackdown. SSF Commander of Mazandaran Province, Morteza Mirzaii announced that 47 locations in Northern Iran would be monitored by the SSF, including parks and recreational areas.

Further crackdowns would target clothing manufacturers and outlets, especially those selling open-front manteaux and manteau dresses. Court orders were sought to seal clothing units according to the Tehran Public Security Deputy Police Supervisor of Public Place, Nader Moradi. Online clothing would further be the subject of judicial orders and legal action under Mr Moradi’s command. In total, 1,185 clothing outlets were visited by Iranian police, 49 units were sealed while another 87 units were given formal warnings against selling open-front clothing. Additionally, 23 units have been filed against and are required to appear before a judiciary.

In 2019, the Iranian government announced the implementation of ‘Observer Plan #1’ aimed at identifying and prosecuting women drivers who failed to wear a veil. A spokesperson for the Ardabil Province claimed that women drivers’ appearance must match their ID at all times, failure to do this will result in confiscation of their registered vehicles.

Violence against protesters would peak in the second half of 2022 with the death of Mahsa Amini. Ms Amini was arrested on September 13 for not adhering to Iran’s strict dress code. She was taken to Vozara Detention Centre where, per UN experts, she was allegedly tortured. She later collapsed after 3 days in police custody and was transferred to a local hospital yet passed away shortly after. Ms Amini’s cause of death has been both confirmed as one cause yet redacted due to another. Initially, leaked documents showed that Ms Amini had suffered several blows to the head, causing a bilateral diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. She also suffered from pneumonia, secretion retention and superimposed infection allegedly caused by brain trauma. After the leak, official statements from an Iranian coroner showed that Ms Amini did not die from blows to the head, but from cerebral hypoxia or a decrease in oxygen supply to the brain.

The death of Ms Amini sparked dramatic, internal outrage within Iran. On the day of her death, thousands of protestors took to the streets in Iran’s main cities. While peaceful in nature, Iranian police demonstrated a similar disproportionate and unnecessary attitude towards these protestors as they had with previous protestors. Testimonies claim that protestors were fired at with birdshot rounds and other metal pellets, resulting in at least 8 deaths and dozens more injured and arrested.

Freedom of Religion, Conscience and Thought

Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) to which Iran is customarily bound, guarantees freedom of religion, conscience and thought. This Article encompasses a wide array of beliefs whether they be personal, religious, political or any other individual or group conviction.

It is often interpreted as allowing action and representation of belief structures by granting the liberty to hold such beliefs. It does not place restrictions on the right to believe in any belief structure but is notorious for restricting attacks against this freedom. For example, the Hijab ban imposed by France in 2010 was found to be inadmissible as it contradicted Article 18. The ban did not aim to ensure any genuine objective such as national security, public health or public order could be obtained as per Article 18 (3). What constitutes a ‘genuine’ objective is very broad. For example, imposing movement restrictions to calm the spread of COVID-19 is a proportionate response to hinder the spread of a dangerous virus on public health grounds. Regarding religious expression, any restriction on grounds found in Article 18 (3) must be based on principles not stemming from a single tradition or interpretation. The strict Islamic interpretation of compulsory veiling can be seen through the lens of a ‘single tradition’ and thus can be considered arbitrary. Additionally, any limitations must have strict, directly related and proportionate predications. This means that a direct, causal link between women not wearing the veil and Article 18 (3) grounds must be made. This cannot be achieved. Failing to wear a veil offers no feasible threat to national security but only to Iran’s societal integrity as an Islamist state. Furthermore, it doesn’t offer any feasible precedents for being necessary as imposing some danger on public health/moral grounds. A moral argument can be made from an Islamic perspective, yet the imposition of a human rights violation outweighs Iran’s ability to enforce it.

This demonstrates the proactive protection of expression, not the hindrance or expectation of expression, yet the same logic can be applied to compulsory legislation.

1. Public-Private Sphere Dichotomy

The manifestation of religion, such as choosing not to wear a veil is equally protected in both the public and private spheres. This creates an individuality to religious expression that steers away from communal representation and towards personal expression. This concludes that in accordance with General Comment No.22 from the UN Human Rights Committee and Article 18 UDHR that the choice to remove a veil in one’s home garners the same international protection as removing a veil in public life. Therefore, Iran’s legislative insistence to force women to wear a veil violates international law in this regard.

2. Non-Discrimination and Equality

Non-discrimination and equality are intrinsically linked within the International Covenant for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) and restricts:

“any distinction, exclusion or restriction made on the basis of sex which has the effect or purpose of impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment or exercise by women, irrespective of their marital status, on a basis of equality of men and women, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural, civil or any other field”

This restriction further applies to overcoming institutional barriers based on religious or cultural traditions which in turn prevents women from participating in society in any form. It’s clear that the compulsory veiling laws are in breach of this. The barrier has not only been institutionalized from a religious standpoint but written into hard law that is strictly enforced. Therefore, women in Iran are heavily restricted from participating in public life unless they strictly adhere to religious traditions they might otherwise disagree with.

Conclusion – An emerging 2nd Afghanistan?

There are clear, stark similarities between Iran and Afghanistan’s approach to women’s rights and expression. While both governments are motivated by different theological interpretations and cannot be compared in that sense, their crackdowns both mirror each other in malicious ways.

Effective control becomes exacerbated during protests, to which both states have enforced violent, disproportionate methods of policing these. Enforced disappearances and arbitrary arrests have occurred in both states, including mysterious deaths or injuries during police custody. The new crackdowns imposed by Iran are potentially leading to a greater social crackdown as seen in Afghanistan. Women may be banned from returning to work, gaining employment or forced out of education as a result of their association with the anti-veiling laws, something already seen since the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan. In essence, Iran may be on a direct path to not just violating freedom of religious expression but potentially a long list of civil, political, social and economic rights.

Image: Symbolized image of Vida Movahed’s protest (Source: Hosseinronaghi via CC BY-SA 3.0)

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research