14 February, 2023

By Luke Austin – Junior Fellow

Japan has been an instrumental actor in nuclear non-proliferation since the Cold War. This stance has been influenced heavily by its own experiences, specifically the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki by the United States in 1945. However, in the changing global environment, could Japan one day become a nuclear power?

During the Second World War, Japan conducted its own nuclear weapons programme. The “Ni-Go” project, for example, was tasked with enriching uranium by means of thermal diffusion. This programme, like that of Japan’s Axis partner Germany, ultimately failed in achieving its goals. Japan is the only country to have been subjected to a nuclear attack. The atomic bombings, along with other traumatic events such as the Battle of Okinawa, are regarded collectively as a driving factor for Japan’s notable domestic pacifist sentiment. Japan is a signatory of the non-proliferation treaty (NPT), and has also devised its own three non-nuclear principles which prohibit the possession, production and import of nuclear weapons. These moves are credited to the work of Prime Minister Eisaku Sato in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The NPT, however, was strongly opposed by opposition parties and even some within the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) for a mixture of economic and ideological reasons. It was only after a series of inter-party compromises that Japan ratified the NPT in 1976.

Nuclear weapons have been derided by much of the Japanese public. The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki not only led to the instant deaths of around 125,000 individuals and massive structural damage, but they also created a new social class- the hibakusha. Literally translated as ‘explosion-affected persons’, the hibakusha soon mobilised into social movements which fiercely campaigned for compensation from the Japanese government and an apology from the US government in the post-war period for the suffering they had experienced as a result of the atomic bombings. The hibakusha also experienced considerable discrimination, particularly in terms of employment and marriage. One popular explanation for this discrimination draws upon the idea that radiation became known in Japan as a “polluting, defiling substance”: this conception of radiation draws upon certain Buddhist and Shintoist belief and value systems deeply-rooted in Japanese society which make a huge distinction between ‘purity’ and ‘pollution’. This is why, for example, not only first-generation hibakusha but often also their descendants face difficulty in finding partners for marriage over fears of “passing on” radiation-related genetic damage to future generations. Paradoxically, the hibakusha themselves came to be regarded by many in Japan as human representations of the pain endured by Japan during the war and subsequently influenced pacifist as well as anti-nuclear sentiment, despite popular discrimination and lack of government support.

Aside from the atomic bombings, domestic opposition to nuclear weapons was reinforced by the 1954 US Bikini Atoll nuclear tests that impacted the health of Japanese fishermen. The US stationed its nuclear weapons on Okinawa until 1972, and this led to numerous protests from a range of social movements and even political parties such as the now-defunct Okinawa People’s Party (OPP). Another key development was the so-called ‘Kobe formula’ implemented by the Kobe municipal government in 1975, which introduced mandatory certification by foreign vessels that they were not transporting nuclear weapons if they intended to dock in Kobe port. The aforementioned events contributed to the formation of a coherent and already deeply ingrained anti-nuclear discourse that predominated within Japanese society by the late 1980s. The Japanese anti-nuclear weapons movement had evolved to such an extent by the early 21st century so as to incorporate the global level of anti-proliferation activism. The Japanese NGO Peace Boat has organised international travel for groups of hibakusha and are openly affiliated with the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN).

In order to fully grasp why nuclear proliferation is so controversial in the Japanese context, it must be remembered that even peaceful uses of nuclear energy are subject to much suspicion and criticism. A TV Asahi poll in February showed that 34% of respondents opposed Kishida’s plans for increased use of nuclear energy. Just over a decade on from the 2011 Fukushima disaster, it may well be the case that this traumatic event continues to shape public perception of nuclear power. Studies have revealed that the disaster’s impact extends to the public perception of nuclear energy in other states that were not even affected. If a shift towards increased peaceful nuclear activity proves so controversial, then it is little surprise that so many would be opposed to the idea of nuclear weapons in Japan’s possession.

However, given challenges posed by numerous issues ranging from the growing nuclear threat of North Korea, the conventional military threat posed by China, as well as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, prospects for a shift in Japan’s nuclear weapons policy continue to change in the most dynamic fashion. In March 2022, the late former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe requested the US reinstall its nuclear weapons on Japanese territory in the face of such threats. However, Japanese support for US nuclear weapons on the country’s territory does not necessarily equate to Japan developing and possessing its own nuclear weapons. In fact, the protection offered by Japan falling within the US nuclear umbrella has been given as a reason for its refusal to sign the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), as it cannot risk being seen to oppose the very system which protects it from the nuclear threat posed by North Korea. However, it has been shown that the majority of the Japanese population do in fact support Japan joining the TPNW. In essence, this is perhaps one of the key indicators that anti-nuclear sentiment in Japan remains strong.

In addition, there is the question of whether the resources currently possessed by Japan could be used for the development of a nuclear weapons programme. Thanks to its controversial yet advanced nuclear energy technology and know-how, it has been estimated that it could take a mere one-to-two years for Japan to manufacture small-scale array of nuclear weapons. However, such a process would most likely be impossible without the modification of civil nuclear reactors.

The potential trajectory of Japan’s possible nuclear path could be shaped by the aspirations and policies of not only potential adversaries such as North Korea, China and Russia, but also those of its own allies. Heightening doubts as to whether the US is still able to fulfil its security obligations to Japan within structures such as the US-Japan Security Alliance have been cited as part of the rationale behind Japan’s remarkable military build-up in recent years. Such doubts could continue to mount in the face of a US withdrawal from the Indo-Pacific, for example, in the case of the US losing a war with China. Alternatively, there is the potential return of Donald Trump or a Trump-like figure into the White House who could then go on to neglect US allies via adoption of a more isolationist foreign policy. Such situations would most likely lead to Japan’s military build-up including the acquisition and development of its own nuclear weapons. There is also the South Korean factor: as recently as mid-January, President Yoon Suk-yeol announced for the first time that his country would contemplate not only the redeployment of US nuclear weapons on its territory, but also the development of its own nuclear arsenal should the threat posed by North Korea continue to increase. Should South Korea decide to take such action, then Japan might be prompted to follow in the same direction so as for its contributions to regional security to not appear insufficient: Japan’s ‘chequebook diplomacy’ during the Persian Gulf War and inability to contribute military personnel have served as sources of humiliation for numerous Japanese policymakers.

While Kishida is preoccupied with difficulties ranging from impediments to economic reform and a shrinking population as well as local elections due to be held in April, increased civilian nuclear energy use intended to avert an energy crisis may lead to a higher incentive for Japan to adopt nuclear weapons based on uranium-enrichment capacities, and that is not to mention the ever-growing geopolitical tensions facing Japan as a key US ally in the Indo-Pacific region. Nevertheless, given continued popular opposition to nuclear weapons and proliferation in general, the triggers for Japan’s development of nuclear weapons would have to be of a certain magnitude in terms of the threat to be perceived by Japan- such scenarios could range from an all-out US withdrawal from the Indo-Pacific region to confirmation of a North Korean nuclear attack on Japan or even a Chinese invasion of the disputed Senkaku Islands. Recent research suggests that while negative attitudes towards nuclear weapons continue to be prevalent in Japan, such attitudes are not absolutely unyielding and a hypothetical deterioration in Japan’s security environment could well lead to an increased rate of support for Japan’s acquisition of nuclear weapons. What might be likelier are repeated calls for the redeployment of US nuclear weapons on Japanese territory, echoing Abe’s proposals for some sort of nuclear sharing akin to that practiced by the US and its NATO allies.

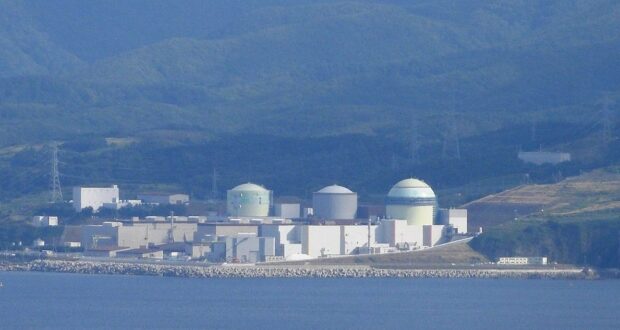

Image: Tomari Nuclear Power Plant (Tomari, Hokkaido, Japan) (Source: Mugu-shisai via GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2)

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research