10 August, 2023

By Luke Austin – Junior Fellow

Japan and the United Kingdom share bilateral relations that date back to at least 1600. The English navigator William Adams, who came under the service of the warlord Ieyasu Tokugawa and became fully assimilated in Japanese public life, greatly contributed to the development of maritime cartography in early 17th-century Japan. It was also during this period that English merchants competed intensively with their Dutch rivals to secure trade with Japan. In 1902, the Anglo-Japanese Alliance was signed: this pact has been credited with allowing Japan to prevent Russian territorial expansion in Northeast Asia for much of the early 20th century. The United Kingdom subsequently supported Japan in its 1904-1905 war against Russia. British influence in that conflict was particularly notable in the Imperial Japanese Navy, as many Japanese naval officers were trained in Britain and most Japanese naval battleships of the period had also been constructed in UK shipyards. Under the framework of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, Japan participated in the First World War on the side of the Triple Entente containing the UK: it was primarily Japanese military forces which captured the German naval base in the colony of Tsingtao on the eastern Chinese coast. The two countries maintained the alliance for two decades until Canada and the US pressured the UK to refrain from renewing it. Both states were involved in the Second World War on opposing sides, engaged in bitter fighting against each other in the Pacific Theatre for almost four years. Over the Cold War and post-Cold War periods, however, bilateral ties have been strengthened considerably, with Japan becoming one of the UK’s closest partners in Asia by the early 21st century.

Despite profound changes in their respective domestic political situations, such as the 2015 revision of the Japanese constitution’s Article 9 and the UK’s decision to withdraw from the European Union following the 2016 ‘Brexit’ referendum, UK-Japan bilateral relations have retained a high level of importance for both parties. This is especially so given the rise of Russia and China, both of which factor heavily in the two parties’ strategic outlooks. What are the prospects and challenges for this dynamic, yet very much understated, relationship?

From a British perspective, the consolidation of bilateral relations with Japan is part of its tilt towards a comprehensive Indo-Pacific strategy. This trend became particularly pronounced following Dominic Raab’s visits to Vietnam and South Korea in September 2020. Following his return to the UK, Raab emphasised the growing importance of the Indo-Pacific region for both the UK and the G7 in a set of issues ranging from economic cooperation to the COVID-19 pandemic in an October 2020 House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee meeting. It has been argued by some that such a shift in British foreign policy represents a wider ‘Global Britain’ paradigm which is also supplemented by a changing view of China as a threat. While this ‘Global Britain’ strategy has been deemed by an expert writing for the Kremlin-affiliated Russian International Affairs Council (RIAC) as a ‘neo-Victorian’ and ‘imperialist’ project fuelled by a romanticisation of the UK’s colonial past and potentially unsavoury intentions, such myths can be easily dispelled. First, many prospective partners are not former British colonial subjects. Vietnam, with which the United Kingdom-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement was signed in December 2020, is in fact a former French colonial possession. In the context of UK-Japan bilateral relations under the ‘Global Britain’ framework, Japan was along with Thailand never colonised by an external power. The ‘Global Britain’ approach is not merely an instrument for the UK to conduct trade and cooperation with its Commonwealth partners, but rather to transcend pre-existing formats. Second, it is natural for any state to pursue cooperation with other states, be it economic or political, regardless of the nature of their respective histories. This has been demonstrated by the work of scholars such as Duncan Snidal, who has shown through his work on the concept of “constant returns” that there is a tendency for the benefits of inter-state cooperation between any two states to be proportional to their respective sizes and also to be shared equally.

From a Japanese perspective, bilateral relations with the UK hold great importance from both a political and an economic point of view. The UK has been identified as a vital regional hub for Japanese soft power projection in Europe. Soft power resources, according to the cofounder of neoliberal IR theory and pioneer of the concept of ‘soft power’ Joseph S. Nye Jr., differs from ‘hard power’ in that it holds a more co-optive rather than coercive nature while resources include “cultural attraction, ideology, and international institutions”. The primary reason for soft power’s central position in Japanese foreign policy has been identified as Japan’s postwar pacifist constitution, which subsequently rendered it more difficult for Japan to develop its hard power resources. At least, this has been the case until the 2015 revision of the constitution’s Article 9 championed by the late Shinzo Abe, which in turn permitted the dispatch of Japanese military personnel to participate in combat missions overseas as well as allow more flexibility for collective self-defence. The importance of the UK for Japanese soft power projection became clear in the summer of 2018, when a ‘Japan House’ was opened in the Kensington area of London, serving as an establishment spreading knowledge of Japanese culture and technology through exhibitions and workshops. Moreover, the London Japan House is alongside its counterpart branches in Los Angeles and Sao Paulo administered by the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA).

It is also worth briefly exploring the nature of bilateral UK-Japan trade. Between 2019 and 2020, UK exports to Japan decreased by almost 30%. Japanese exports to the UK also decreased by 22% in the same period. Multiple reasons have been proposed for this notable slump, with these ranging from Brexit forcing Japanese corporations to reevaluate their activities in the UK (which had been historically used as a ‘bridge’ into the rest of the EU) to the UK economy being characterised as a predominantly services-based economy. The COVID-19 pandemic also posed serious implications, including reduced economic activity and the disruption of supply chains. What is particularly unsettling is that these negative trends continued despite the United Kingdom–Japan Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) having been brokered between then-International Trade Secretary Liz Truss and Japan’s Foreign Minister Motegi Toshimitsu in September 2020 before being signed in October. The UK-Japan CEPA, while defended by some as an initial stepping stone towards the UK’s eventual entry into the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), ultimately delivered little in terms of economic benefits for the UK in the sense that it was hardly any different from the trade deal applied between the UK and Japan when the former was an EU member-state. More recent times have reflected a more promising trajectory. Between April 2022 and April 2023, Japanese exports to the UK increased by 15%. According to the latest statistics available from Japan’s Ministry of Finance, Japanese exports to the UK are dominated by automobiles, electrical appliances and machinery parts such as prime movers. The Office of National Statistics (ONS) lists mechanical power generators, non-ferrous metals and medicinal and pharmaceutical products as the UK’s primary goods exported to Japan in the first quarter of 2023. Japan was also named as the UK’s fifth largest investor with up to £92 billion invested in the UK economy in a 10 Downing Street press release issued in May.

Both countries enjoy reputations as renowned US allies. While the UK is a long-standing member-state of NATO, Japan is considered a major regional partner in the Indo-Pacific region alongside Australia, New Zealand and South Korea. One way in which the nature of UK-Japan relations could be defined in the future is by their greater cooperation within the framework of NATO or related organisations such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad). On one hand, Japan’s entry into NATO is unlikely for several reasons: Japan is not eligible to join NATO due to its geographical location, Kishida has denied any plans for Japan’s entry into NATO and there are also fears that this would cause unnecessary friction with China. On the other hand, this does not change the fact that NATO has expressed an increasing level of attention to developments in the Indo-Pacific. It has largely been credited to the initiative of NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg that Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand were invited to the July 2023 NATO Summit in Vilnius and that a joint statement involving all parties was delivered. Furthermore, there have been proposals recently expressed by Japanese officials such as Japan’s ambassador to the US Koji Tomota for the establishment of a NATO liaison office in Tokyo. These proposals have faced fierce opposition from France in particular. Nevertheless, Stoltenberg has affirmed that the possibility to establish such a facility still remains: the symbolic significance of such a move is difficult to exaggerate. Given milestones such as the first joint military exercise between the British and Japanese air forces in October 2016, the first joint military exercise between the British Army and Japan Ground Self-Defence Forces (JGSDF) in October 2018, joint naval drills in August 2021 in the vicinity of Okinawa and a joint paratrooper exercise also involving Australia and the US in January 2023, it is quite clear that greater NATO-Japan cooperation will equate to greater UK-Japan security cooperation.

Another multilateral format in which the UK and Japan are actively involved is the G7. The G7 has been identified as a broad yet effective alliance to compete with its rival BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) and China itself, so much so that the 2021 Carbis Bay G7 Summit has been referred to by one German scholar as “a turning point in international relations”. Both states have also used the G7 format to rally together in recommending strategies for separate organisations such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

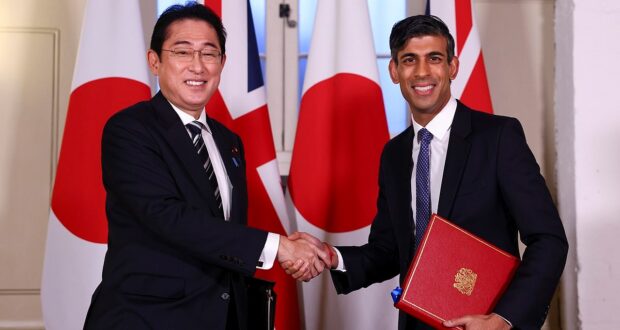

The prime ministerships of Rishi Sunak and Fumio Kishida of their respective countries appear to have heralded a spate of developments in bilateral UK-Japan relations. During Kishida’s January 2023 visit to the UK, the two leaders signed the UK-Japan Reciprocal Access Agreement (RAA) at the Tower of London, which effectively permits the deployment of each state’s militaries on each other’s territory. Two main reasons have been given by the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) for the signing of the RAA: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and heightening tensions with China in the South and East China Seas. Such an agreement has been deemed by 10 Downing Street as the most significant of its kind since the 1902 Anglo-Japanese Alliance. Sunak and Kishida also discussed the UK’s potential entry into the CPTPP. Such a venture is of vital importance considering a pronounced slump in UK overall trade and gross domestic product (GDP) growth in most areas between 2019 and 2022 as a result of Brexit and the COVID-19 pandemic. On 16th July, this indeed became a reality: Secretary of State for Business and Trade Kemi Badenoch signed the CPTPP accession protocol for the UK during a CPTPP Ministerial-level Commission in Auckland.

In light of such developments, the future of UK-Japan relations appears promising. With bilateral trade increasing again alongside far-reaching advances in security cooperation, this appears to be a trajectory that will not terminate anytime soon. One additional format in which UK-Japan bilateral relations could develop further is the United Nations (UN). Japan has sought a permanent seat at the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) since the 1970s. The UK holds a permanent seat on the UNSC. Moreover, it has alongside France supported reform of the UNSC so as to include additional members, including Japan. This has most recently been reflected in comments made by UK Ambassador to the UN Barbara Woodward in November 2022 and again in July 2023. Even if Japan faces considerable hurdles in gaining a permanent UNSC seat such as opposition from other pre-existing members such as the US based on what they perceive as a threat to their authority, continued UK-Japan cooperation in such moves could represent an elevation of this work from the bilateral to the multilateral.

Image: UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak meets Japan’s Prime Minster Fumio Kishida for a bilateral meeting (Source: 10 Downing Street via CC BY-SA 2.0)

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research