November 28, 2022

by Sam Biden, Research Assistant

Death Penalty Statistics 2021

As of 2021, a third of states have not abolished the death penalty in law or in practice. This resulted in 579 public, state-sanctioned executions. This figure is most likely higher as states such as China are reluctant to reveal their official statistics and operate capital punishment through confidential means.

In the Americas, the USA were responsible for all 11 executions sanctioned in 2021 resulting in the 13th consecutive year that all other regional states had no executions. 25 new sentences were handed out in the USA, Guyana and Trinidad and Tobago. Asia-Pacific figures cannot be accurately verified as the primary executing states (Bangladesh, China, Japan, North Korea & Vietnam) rarely publish official figures relating to capital punishment, although Japan did admit to hanging at least 3 men. Across the region, 819 new death sentences were handed out in 16 states, a 58% rise over 519 sentences the prior year. In Europe & Central Asia, one execution and sentence were confirmed in Belarus, one of the only states that are currently not a member of the Council of Europe, which has formally abolished the death penalty. In the Middle East and North Africa, 520 executions were recorded in 7 states (Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Syria, United Arab Emirates and Yemen), an increase of 19% since 2020. Additionally, Syria ordered a mass execution in October, resulting in 24 deaths and 5th place for the largest recorded execution by deaths in 2021. Sub-Saharan Africa doubled their rate of executions since 2020, amounting to 33 executions. This sharp rise reflects the ongoing instability in both South Sudan and Somalia. 373 new sentences were confirmed in 19 states, another increase of 22% since 2020.

The right to life is embodied in international, domestic and regional documents. It protects the right of an individual to be free from arbitrary deprivation of life. The term arbitrary ensures us that the right to life is not absolute and can be derogated from. For example, state police forces typically have procedures that allow for the deployment of lethal force when confronted with a threat to life, this would be considered a legitimate derogation from the right to life. The deprivation of life has broadly been agreed upon as lawful per both international and domestic law. This lawfulness is deemed by the avoidance of inappropriateness, injustice, a lack of predictability and due process during both the sentencing and executing stages. Additionally, the arbitrary clause allows the death penalty to gain some legal legitimization but is only allowed in extreme circumstances with specific safeguards.

ICCPR Article 6 lays out these circumstances and safeguards in more detail. Firstly, the death penalty may only be imposed for the most serious crimes. Although these crimes are not unanimously agreed upon, they typically involve murder, war crimes and genocide. Crimes that do not directly cause the death of an individual such as white-collar crimes, armed robbery and corruption cannot be used to impose the death penalty. Additionally, the death penalty may only be granted through a final judgement from a competent court, it cannot occur through government direction. Second, anyone sentenced to the death penalty automatically has the right to file an appeal or pardon from the sentence which can be granted in any case. Finally, the death penalty may not be imposed against anyone below the age of 18, against pregnant women or against those without an equal ability to defend themselves such as those with intellectual disabilities. Additionally, the right of states to withdraw their ratifications to the Second Optional Protocol aiming to abolish the death penalty is revoked upon ratification. Once a state has ratified the Protocol, it cannot reintroduce the death penalty under any circumstances, leading to many high-number executing states delaying or refusing ratification entirely.

As demonstrated, the protective circumstances the right to life offers has clear, strict limits. Through this method, true abolition of the death penalty cannot be achieved as states can always continue the use of the death penalty in line with the aforementioned safeguards. Therefore, a new path must be analyzed where the right violated cannot be derogated from in any circumstances.

The Death Row Phenomenon & Freedom from Torture (Article 7 ICCPR)

This pathway can initially be achieved when comparing the psychological effects of being detained on death row, formally known as the ‘death row phenomenon’ in the medical literature, with a torturous threshold found in international treaties and jurisprudence.

The negative psychological effects of being on death row primarily relate to the duration or delay between sentencing and execution. Often times, those facing the death penalty will be incarcerated for years and sometimes decades before execution, particularly in the US, with an average sentence length of 18.7 years. The death penalty inevitably causes cruelty through delay, while this does not amount to torture, it still falls within Article 7 more broadly. These delays can happen for a variety of reasons. For example, appeal cases are often immediately filed in most countries so the defence attorneys can attempt to have the sentence overturned, revoked or reduced to a life sentence instead. Another instance relates to general administrative functions such as inmate processing, organisation tasks for the execution itself as well as handling inquiries into the closed case that may indicate a miscarriage of justice.

The medical literature is very clear on the nature of the death row phenomenon. For example, one criminologist studied and interviewed 35 condemned prisoners who had been handed death sentences for serious crimes in Alabama, USA. The researcher found that the overwhelming majority of the inmates were primarily preoccupied with the length of time spent on death row, not the fear of execution itself. Additionally, the isolated conditions often associated with maximum security, lead many participants to feel totally abandoned, formally known as the ‘death of personality’. This concept is based upon the deterioration of both the mental and physical health of the participants. Some issues include the development of depression, a disconnect from reality, a reduction in overall mental capacity as well as a deterioration of overall physical health.

As well as academic support, the death row phenomenon has a history in jurisprudence, particularly in US law. Justice Miller states:

‘When a prisoner sentenced to death by a court is confined in the penitentiary awaiting the execution of the sentence, one of the most horrible feelings to which he can be subjected during that time is the uncertainty during the whole of it… as to the precise time when his execution shall take place.’

The US Supreme Court has echoed the medical literature as well, likening being held on death row as beyond the cruelty of the execution itself. Over in Europe, the ECtHR agreed with US jurisprudence in the infamous Soering v. UK case. Jens Soering murdered his parents alongside an accomplice. After fleeing to the UK, Mr Soering was charged with fraud and was due to be extradited to the US for the death penalty in Virginia, yet the ECtHR ruled this unlawful. The court unanimously agreed that the delay from sentencing to execution contradicted Article 3 ECHR (Freedom from Torture).

The Issue

While the medical literature shows significant evidence of inhumane, cruel and torturous feelings held my inmates as well as jurisprudence confirming this violates Article 7, states can still circumvent this. This circumvention arises when the legal framework that allows the death penalty merely takes on a more rapid approach. For example, death sentences could be arranged to be fast tracked rather than drawn out, this avoids the primary issue of delay during sentencing that amounts to a violation of Article 7. Additionally, so long as the new legal framework cannot be considered arbitrary in any form, states would not be under any obligation to abolish the death penalty domestically.

A Potential Solution

One potential solution is to view a violation of Article 7 through the death row phenomenon as a risk rather than an observation. This concept is drawn from the principle of non-refoulement, a customary rule of refugee law. Non-refoulement restricts a state’s ability to extradite an individual if there is a risk they may be persecuted in the arriving state, this includes the death penalty. By viewing the sentencing and incarceration processes through this lens, we can assume that there will always be a risk, even if insignificant, that an inmate may suffer from the death row phenomenon. In essence, the death penalty as an action could remain lawful under Article 6 but the essential process required to perform this action would be the element that violates Article 7.

One argument against this is the use of fast-track systems mentioned prior, allowing for a reduction in delays. However, the medical literature does not indicate a strict timeframe in which the death row phenomenon automatically begins to occur, it is subjective and based on the personality traits and overall mental and physical stability of each inmate. Therefore, without evidence to support that each individual inmate could handle a fast-track system (such as 4-12 weeks), the assumption that an inmate could begin to suffer from the death row phenomenon in such short periods is feasible. Additionally, appeals are an essential component of every legal system even when not successful. Appeals can take months to years to complete and are often immediately filed upon conviction by the defending counsel, potentially damaging the legitimacy of a fast-track system even more.

Furthermore, welfare assessments could be conducted on behalf of each inmate sentenced to death to attempt to avoid violation of Article 7. In theory, this could still lead to a violation under the notion of viewing a violation of Article 7 as a risk and not an observation. In particular, any initial welfare assessment does not provide any guarantee that an inmate wouldn’t suffer from the death row phenomenon during their incarceration.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the only feasible way to force states to abolish the death penalty is to view the sentence itself as placing any potential inmate in a state of torture, inhumane or cruel treatment or punishment. This can be achieved in two different ways.

First, this new concept can be hard codified in the form of an additional Protocol to the ICCPR. While these are often optional, meaning states are not obligated to ratify it if they disagree with the premise, the nature of violating Article 7 already has a customary status and is wholly regarded as non derogable. In essence, hard codification would bind any reluctant states regardless of whether they ratify the additional protocol. Second, a combination of supportive commentary from the UN General Assembly, International Criminal Courts/Tribunals as well as input from the OHCHR could outline the violation of Article 7 as valid without the need to draft what are often lengthy and hyper-complex international documents. These kinds of collaborative discussions are how new norms of international law are discovered in the first place, leaving a strong chance that an Article 7 interpretation could be accepted.

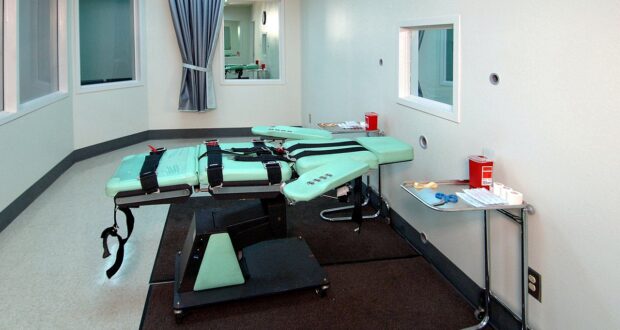

Image: A gurney at San Quentin State Prison in California formerly used for executions by lethal injection

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research