By Raphael Levy

10th July 2014. Security and Defence, Issue 3, No. 2.

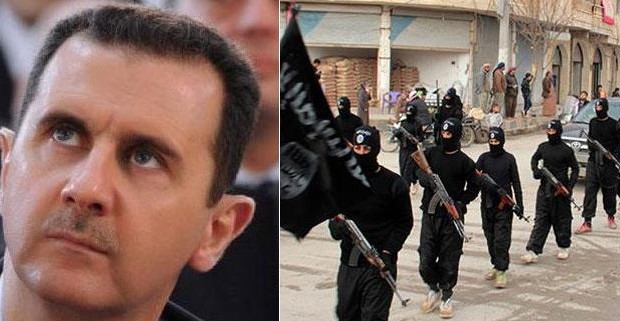

America’s commitment to the principle that one’s enemy’s enemy is one’s friend has come back to bite them on more than one occasion, and now Bashar Al-Assad is beginning to realise that even just leaving one’s enemies to fight it out can be problematic. Back in 2011 Assad released a number of jihadist prisoners that went on to be part of ISIS (Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham), now simple called the Islamic State or IS, since they declared a caliphate last week. This release was a tactical move to aid Assad’s efforts against rebel forces, possibly either allowing him to place blame for the revolution on Islamists (which is rather difficult to do if they are all in prison) or even lead to fighting between the rebels and newly released Islamists.

Assad calculated that the West was less likely to intervene in Syria if it could be “shown” that the revolution was the result of an Islamist uprising or that the rebel forces had been infiltrated by radicals. Consequently, the civil war is thus portrayed as the regime engaged in a battle against forces that oppose democracy, freedom and everything the West stands for rather than more moderate rebel forces. If Western countries can be persuaded of the former, namely that the rebel forces are divide and therefore providing weapons to them could potentially lead to arming radical Islamists, this option becomes much less appealing and therefore less likely.

Moreover, ISIS fighters engaged in fighting against exactly those rebel forces that Assad was attempting to defeat. Whilst intelligence may also suggest that Assad was relatively more direct in his support for ISIS against the rebels – The Telegraph, for example, reports that covert oil deals took place, what is clear is that Assad was at least happy to indirectly support ISIS. The relationship became somewhat mutually beneficial with Assad refraining, until recently, from bombing ISIS strongholds and perfectly content to let the rebels and Islamists fight against each other, weakening both sides.

It is not necessary to engage in further speculation over the extent of the relationship in the past between Assad and ISIS – articles referenced here offer intelligence and arguments on that matter. Rather, what is clear is that Assad underestimated ISIS and their capabilities. It goes without saying that he never imagined ISIS establishing a Caliphate partially in Syrian territory and Assad is now being forced to lie in the bed he made for himself. By happily allowing ISIS and the rebels to fight it out and being willing to use ISIS and other jihadist groups in his propaganda war, he has unintentionally allowed the situation we now see developing before our eyes to occur. Assad’s actions are a direct cause of the rise of ISIS and it seems he has realised all too late the implications of this for his regime in Syria.

It may have been the case that ISIS/IS were opposed to the rebel forces (for all together different reasons to Assad), but Assad has finally realised that their rise is more of a threat to his regime than of benefit. What is now becoming apparent for Assad, especially with the establishment of the Caliphate, is that IS are a serious organisation rather than merely a convenient foe. Bombing raids by Syrian planes on IS held areas and strongholds may represent the end of what was an uneasy, mutually beneficial relationship between the two.

Whilst Assad may have initially had some success in dividing rebel ranks and forcing suspicions over the Islamist links of the rebels, the swift advances of ISIS through Iraq has forced action to be taken. Obama has recently asked Congress for $500 million to train and equip “moderate” rebel forces. Whilst this is also aimed at supporting those fighting Assad, it is the stunning and swift rise of IS in the area that is forcing this move. The White House suggests that the aid will help those fighting forces aligned to Assad but also, and crucially, help counter Islamic militants, specifically IS. The rebels have found themselves increasingly fighting both Assad’s forces and IS (and other Islamist groups), severely weakening their capabilities and Obama’s position (of arming the ‘moderate’ rebels) has been strengthened with the establishment of IS as distinct from the rebel forces.

The rise of IS is ironic for Mr Assad. The initial move to divide the rebels and make it seem as though they had been infiltrated by Islamic extremists may have been successful in deterring Western support for rebel forces. It is probably also the case that IS weakened the rebels and left them fighting both IS and Assad’s forces, to Assad’s initial benefit. However, the rise of IS has left the West with only one option and that is to arm the rebels fighting IS, both against IS themselves, but also Assad’s forces. By allowing the rise of IS, a rise he may have never envisaged, Assad helped make a clear distinction between the more moderate rebels (i.e. those fighting against IS as well as his forces) and the radical Islamists he sought to infiltrate the rebels with. Suddenly arming the rebels is slightly more appetising.

Raphael Levy is contactable at:

Raphael.Levy@hscentre.org

Please cite this article as:

Levy, R. (2014). ‘Assad’s policy of boosting ISIS has backfired’

Human Security Centre, Defence and Security, Issue 3, No. 2.

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research