22 December, 2020

By Irena Baboi – Senior Fellow

On 20 January, Joe Biden will take office as the 46th president of the United States, having defeated Donald Trump in the November presidential elections. The leaders of the Western Balkan countries were unanimous in congratulating Biden for his win, and many took care to remind him of the strong ties between Washington and their respective countries. Some of these leaders, however, would have preferred a different outcome in the elections, and were counting on a continuation of the laissez-fare foreign policy strategy for which the previous administration had become known. Donald Trump’s seeming lack of interest in the region, coupled with his soft spot for nationalist leaders, meant that governments in the Western Balkans could make self-interested decisions without fear of repercussions – a state of affairs that is bound to change now that there is a new leadership in the White House.

Under the Trump administration, governments across the Western Balkans have more or less been left to their own devices. Serbia’s growing relationship with China, along with its long-standing obedience to Russia, have remained unchecked by the United States in the past four years. In the last twelve months alone, Bosnian Serb leader Milorad Dodik’s claim that recognition of Kosovo would also demand recognition of Republika Srpska was met with silence from the White House, as was Bulgaria’s threat to block North Macedonia’s long-postponed negotiations for European Union membership. Washington’s lack of coordination with Brussels on political matters, along with an exclusive focus on immediate economic goals, has resulted in very little pressure on Western Balkan governments to make democratic and regional progress.

The Serbia-Kosovo deal reached this year is the perfect embodiment of Donald Trump’s foreign policy strategy in the Western Balkans. On 4 September, in a meeting brokered by US special envoy Richard Grenell, Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic and Kosovar Prime Minister Avdullah Hoti signed an economic normalisation agreement between their two countries. Deemed as “historical” and a sign of Washington’s commitment to the Balkans by the Trump administration, the agreement commits Serbia and Kosovo to building road and rail links to connect their two capitals, and Kosovo to join a passport- and duty-free initiative that is to include Albania, Serbia and North Macedonia. As part of the deal between the two countries, Serbia also agreed to move its embassy in Israel to Jerusalem, which was rewarded with international recognition for Kosovo from Israel. Crucially, the agreement signed by Belgrade and Pristina does not demand recognition of Kosovo’s independence by Serbia – arguably the main step that would lead to real normalisation of relations between the two countries.

Where Donald Trump was in favour of quick foreign policy fixes that would make headlines and could be exaggeratedly deemed as breakthroughs, Joe Biden’s foreign policy strategy and objectives are likely to be designed with a long-term focus. Having served as Vice President for two full terms under the Obama administration, and in the Foreign Relations Committee of the US Senate for three decades, Biden will take office with a wealth of foreign policy experience, along with powerful diplomacy and negotiations skills. The newly-elected United States president is also a strong advocate for close cooperation with allies and international support, and a proponent of diminishing non-democratic influence and involvement in international relations.

With respect to the Western Balkans, Joe Biden has long held a deep interest in the region, and was one of the supporters for the military interventions in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo in the 1990s. Alongside repeatedly stating his commitment to multilateralism and NATO, Biden included his vision for the United States’ relationship with Bosnia-Herzegovina, Albania and Kosovo in his election campaign statements, an important signal of his willingness to engage more meaningfully with the region. If the United States is to restore trust in its leadership – as promised by its new president in the lead-up to the elections – the Western Balkans are the ideal place for Washington to start.

The first important step, and one highlighted by President Biden himself during the election campaign, is for the United States and the European Union to start working together again. If the influence of countries like Russia and China is to be diminished, Washington and Brussels need to be united and consistent in their involvement, and focus on promoting economic growth and democratic progress in the region. History shows that when the United States and Europe act as one, the chances of success are high – and a unified West brings more to the table than an unpredictable East.

In the Western Balkans, the Biden administration has all the tools necessary to achieve successful political and economic transformation. The newly-elected POTUS has a deep understanding of the region, and is all too aware that the carrot and the stick are more effective when there is agreement and mutual support between the European Union and the United States. When Washington and Brussels speak with one voice, the Western Balkan governments listen – they know that, in the long-run, this is their best option.

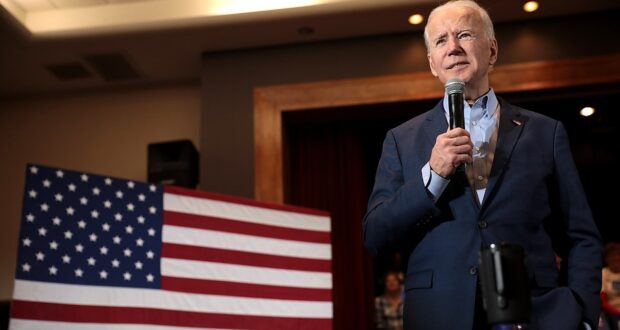

Image: Biden in Henderson, Nevada, February 2020 (Source: Gage Skidmore via CC BY-SA 2.0)

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research