4 July, 2023

By Irena Baboi – Senior Fellow

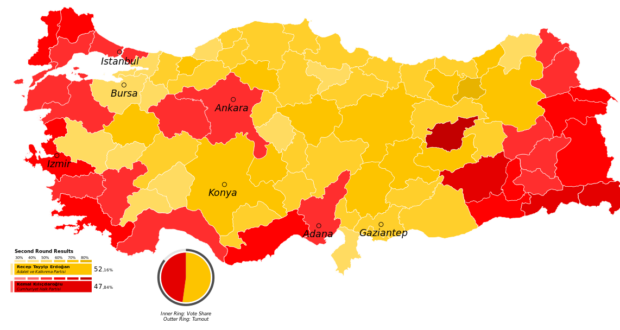

On 28 May, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his Justice and Development Party (AKP) extended their twenty-year rule by winning a joint presidential and parliamentary run-off vote against Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, the unity candidate representing six opposition parties. In power since 2003, first as prime minister then as president, Erdoğan won a further five years as Turkey’s leader in what was a close fought race that ended in a difference of less than five percentage points between the two candidates. The small separation margin, coupled with the need for a run-off vote for the first time since the post of president became popularly elected in 2014, suggest that it is not a comfortable majority of support that Erdoğan and his AK Party can rely on internally. Externally, the long-term leader maintains a careful balancing act between East and West, but this strategy has, at times, made him a difficult and unpredictable ally for both sides. Erdoğan’s strong point, however, is that he has gone beyond the devil both his people and world leaders know in the last two decades – and transformed himself into the devil they need.

On the surface, Turkish President Erdoğan won the elections despite the fact that, for all intents and purposes, the cards were stacked heavily against him. Corruption in Turkey has flourished in the past two decades, human rights and democratic freedoms have been eroded, and any form of opposition and dissent has been significantly supressed. Erdoğan’s mishandling of the economy, moreover, has led to a continuous devaluation of the lira, and Turkey’s central bank has been left with negative foreign reserves for the first time since 2002. The Turkish president’s insistence on pursuing an unorthodox financial strategy – a combination of heavy spending and maintaining low interest rates – saw inflation reach 85% in October of last year, only to ease to a still staggering 44% this April. In early February, devastating earthquakes hit the country, and the government’s slow response increased the death toll to more than 50,000. Despite Turkey’s economic issues, in the run-up to the election, President Erdoğan raised pensions and the salaries of public sector workers, and gave away a free month of petrol and electricity. Turkey’s government has also embarked on the reconstruction of the southern and eastern areas most affected by the February earthquake, effectively ignoring the cost-of-living crisis that has seen the prices of everyday essentials skyrocketing in the last months.

At first glance, the opposition seemingly did everything right too, and ran a campaign that should have swayed the vote in their favour. Six of Turkey’s opposition parties presented a united front at the elections, offered voters an inclusive platform, and provided credible solutions for the country’s most urgent problems. Opposition candidate Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu promised a return to a more orthodox economic policy, and to restore the central bank’s independence. Kılıçdaroğlu also promised to reverse some of Erdoğan’s constitutional changes, return the country to a parliamentary system of government, and give the judiciary back its independence. With respect to other topics important to the Turkish voters – such as earthquake relief and the fight against terror –, Kılıçdaroğlu promised free housing for earthquake survivors who lost their properties in the disaster, and proclaimed that “terrorism will be fought, not negotiated”. As a last-ditch attempt to attract more of the nationalist votes, Kılıçdaroğlu also increased his anti-refugee rhetoric before the run-off vote, and pledged to send Syrian refugees living in Turkey back to their homeland by reaching an agreement with the Syrian government and persuading the European Union to fund the repatriation.

All this, however, would have mattered more if the elections were fair, which is not the case in today’s Turkey. Prior to the elections, as part of the long-term leader’s continuous quest to rid himself of threats to his leadership, Erdoğan’s most popular opponents were either jailed or intimidated with court cases. Istanbul mayor Ekrem Imamoglu, one of Erdoğan’s strongest potential challengers, was accused of insulting members of the supreme election council in a speech made after he won the Istanbul election, and banned from running in the general election. During the campaign, Erdoğan accused his rival Kılıçdaroğlu – whose candidacy was backed by Turkey’s main pro-Kurdish party, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) – of links with Kurdish terrorists, and showed doctored videos depicting Kurdish separatist PKK leaders singing the opposition’s campaign song. Erdoğan also used the unity his opposition attempted to show against them, and argued that the six-party alliance would be unable to agree on anything decision-making-related. As the incumbent leader of the country – and an all-powerful one at that –, Erdoğan used state resources and control of the media to ensure that he had more opportunity to get his campaign message across, while continuously hindering the opposition’s attempts to reach voters.

The above notwithstanding, the reality is also that millions of people chose Erdoğan as their leader. International monitors commented on the lack of a level playing field among candidates during the elections, but in terms of freedom to vote, no irregularities were observed or reported. The turnout for both rounds of voting was over 80%, making it difficult to dismiss the result as fraud, or to argue that it was simply a matter of denying the opposition more of a voice. It is important to note that Erdoğan won a comfortable majority in seven of the eleven areas most affected by the February earthquakes, and nearly 60 percent of the votes of Turkish people living outside the country. In the eyes of many of his citizens, Erdoğan’s track record of revamping public services, developing important infrastructure projects, and overseeing advances in the country’s military and defence industry speaks for itself.

With his Islam- and family-oriented political outlook, moreover, Erdoğan appeals to the nationalists and traditionalists among the Turkish voters, who know that, with the long-term leader in charge, their traditional values will be upheld and defended. As part of his re-election campaign, Erdoğan played on the high anti-refugee sentiment in Turkey, and promised to return to their homeland one million Syrian refugees who are seen by a growing number of nationalists as an economic burden, a security threat, and a danger to the country’s ethnic makeup. The millions of people who voted for Erdoğan also responded to his promise of stability, his pledge that “the era of coups and juntas is over”, and his quest to see Turkey as a strong and independent player on the world stage. While his challenger called on voters to come out and “get rid of an authoritarian regime”, Erdoğan promised a new era uniting the country around “Turkey’s century” – a reference to the country’s centennial this year, but also the neo-Ottoman overhaul that Turkey has experienced under the long-term leader.

Internally, a referendum won by Erdoğan in 2017 allowed him to become Turkey’s first executive president the following year, and virtually eliminate all checks and balances over his leadership. The constitutional changes made before the last general election mean that Erdoğan has the power to appoint vice presidents, ministers, high-level officials and senior judges, dissolve parliament, issue executive decrees, and impose a state of emergency. The Turkish leader has also abolished the post of prime minister and removed the parliament’s monitoring role, and awarded himself the power to declare war and intervene in Turkey’s legal and financial systems.

Externally, Erdoğan’s involvement in international relations has made him a leader that cannot be ignored. Despite providing military aid to Ukraine, the Turkish president refused to join the imposition of sanctions on Russia after the latter’s invasion of Kyiv, and has instead significantly increased trade between his country and Moscow. It was not, however, only Russian President Vladimir Putin that rushed to congratulate Erdoğan for his win – French leader Emmanuel Macron and United States President Joe Biden were also quick to offer their congratulations, expressing hope that the two sides will continue to work together on common bilateral issues.

The multi-vector foreign policy pursued by Turkey under Erdoğan has enabled the Turkish president to maintain constructive relationships with Russia, China and countries throughout the Middle East, and Turkey’s critical role in global challenges that impact Europe and the United States has made Ankara a necessary ally for the West. As a key NATO power strategically located at the crossroad between Europe and Asia, Turkey has solidified its position as a major player in geopolitics in recent years. The European Union relies on Erdoğan to hold his end of the bargain in a deal made during the 2015 migration crisis, and prevent refugees reaching Turkey from crossing the latter’s borders into the European bloc. The United States, meanwhile, needs Erdoğan to approve NATO membership for Sweden, as this would provide important Baltic Sea cover for the North Atlantic alliance against Russia. Officially, Erdoğan will vote in favour of NATO membership for Sweden if the latter changes its alleged soft approach to its Kurdish population – in reality, the Turkish leader will most likely only change his vote if the United States endorses the sale of F-16 fighter jets to Turkey, a sale that was blocked by Washington when Ankara bought a battery of S-400 missiles from Russia.

As mentioned above, part of Erdoğan’s appeal is also that the Turkish leader sees Turkey’s place in international relations as a global power with a seat at all the important tables. In order to achieve this, Erdoğan’s Turkey has taken on the role of mediator, and inserted itself in a number of crucial negotiations. In May, Turkey and the United Nations brokered a deal to restart Ukrainian grain exports and avert global food shortages. Even closer to home, Ankara has also been involved in negotiations relating to North Macedonia’s name dispute with Greece, the normalisation of relations between Kosovo and Serbia, and the internal politics of Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Like all good autocrats, Erdoğan has also created a series of economic, political and social crises, and presented himself as the only one who can solve them. Turkey’s economic issues are the result of his insistence on not following the advice of financial experts, while the influx of refugees is a consequence of Erdoğan’s open border policy. However, when Erdoğan promises economic growth for his country, and that he will return one million Syrian refugees to their homeland, many Turkish people believe him. The strong internal and external roles that Erdoğan has created for himself mean that he is the best positioned to fix the country’s most pressing problems – many of which he created in the first place.

With this win, Erdoğan has defied the theory that the political games played by populist leaders only work in times of economic growth, and when they are played against a fractured and divided opposition. A better explanation would be that, in times of uncertainty, people are willing to sacrifice some of their freedoms in exchange for political, economic and social stability and security, especially if the leader they are supporting has portrayed himself as the best placed to ensure this for them. When it comes to Erdoğan, however, this is not all smoke and mirrors – the long-term leader may just bring his country back from the brink of economic collapse, and fulfil many of his campaign promises. Judging by the number of leaders rejoicing that Erdoğan won, the Turkish president is likely to receive new funding from both his Middle Eastern allies and Russia. The latter has already delayed Turkey’s gas payments, and transferred $5 billion (nearly £4 billion) for the construction of a nuclear power plant in Turkey. According to Erdoğan, unnamed Gulf states have also contributed funds to help stabilise Turkey’s markets, and the Turkish president has agreed to reverse his unorthodox economic strategy. Turkey’s new finance team is expected to double interest rates in an effort to stabilise the country’s economy – and return to a sustainable financial path that could see the revival of much-needed foreign investment.

The system that Erdoğan has carefully built in the last two decades is only functional with him in control. Internally, the long-term leader enjoys the support of not only Turkey’s nationalists and traditionalists, but also those who want to see their country as strong, stable and independent, with a say in international relations. Externally, Erdoğan’s delicate balancing between West and East, coupled with his use of Turkey’s position in the world to its full extent, have turned him into a global leader that cannot be overlooked. This carefully built system, however, is also only functional as long as all these conditions are fulfilled – one significant internal or external failure, and everything could start disintegrating from within.

Image: the results of the second round of the Turkish 2023 presidenral election, with Erdoğan (yellow) dominating rural areas (Source: Randam (edited from original) with data from Anadolu Agency via CC BY-SA 3.0)

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research