9th September, 2017

By Irena Baboi – Junior Fellow

On the 1st of August, Macedonian Prime Minister Zoran Zaev welcomed his Bulgarian counterpart Boyko Borissov to Skopje to sign a historical friendship agreement that aims to put an end to years of tensions between their two countries. The agreement means that Bulgaria and Macedonia will improve economic ties, renounce territorial claims and improve human and minority rights, and that the former now supports the latter’s European integration. The friendship and cooperation treaty also aims to resolve some of the two countries’ differences and, more importantly, acknowledges the fact that having both them and good bilateral relations is possible. This is crucial in a region where historical differences are at the heart of a high number of disputes, as it shows that stalemates in bilateral relations are not permanent, and that concessions are the way forward if internal and international progress is to be achieved.

Bulgaria and Macedonia share close religious, historic and linguistic ties, and Bulgaria was the first country to recognise Macedonia’s independence following the disintegration of Yugoslavia. These close ties, however, have translated themselves into disagreements over language and history, with Bulgaria viewing Macedonian as a dialect of Bulgarian, and the two Balkan nations clashing over the nationality of the 19th century guerrillas who fought to free the region from Ottoman rule. The Zaev-led Social-Democratic Party (SDSM) government’s predecessors, the nationalist VMRO-DPMNE party, were also accused of fuelling anti-Bulgarian sentiments and discriminating against minority ethnic Bulgarians in Macedonia, and the signing of the friendship treaty itself had been shelved since 2012. The 2017 change in government leadership brought a complete overhaul in Macedonia’s political attitude and external outlook – and with Bulgaria assuming the Presidency of the Council of the European Union in January 2018, the overhaul comes at an ideal time.

Bulgaria is not the only Balkan neighbour with which Macedonia seems to be mending ties since the new government came to power. Greece joined Bulgaria in blocking Macedonia’s accession talks with the European Union for years, its main motivation being its objection to the country’s name and belief that Skopje’s use of it could imply territorial claims on the Greek province that shares it. The 27-year long name dispute, however, now seems close to being settled, as immediately after being allowed to form the new government, Zaev sent foreign minister Nikola Dimitrov to Athens to discuss the issue with his Greek counterpart. In light of this historical talk, Foreign Minister Nikos Kotzias declared that Athens will support Macedonia’s European integration, provided that Skopje agrees to a name change – a move to which Prime Minister Zaev has said he is open. The replacement name of the country will have to be subjected to a referendum, but the lack of popular opposition to this decision so far suggests that Macedonia is highly likely to be going into the accession talks with a new one.

Zoran Zaev and the SDSM took over a Macedonia coming out of a two-year political and social limbo. The crisis began in February 2015, when it was revealed that then Prime Minister Nikola Gruevski of the ruling VMRO-DPMNE party had orchestrated the illegal surveillance of thousands of people, including journalists, political opponents and allies, and members of the general public. The government was accused of widespread abuse of power, electoral fraud, media manipulation and embezzlement, and the scandal triggered mass anti-government protests throughout the country. The early parliamentary elections of December 2016 were meant to end the crisis, but neither the VMRO-DPMNE nor the SDSM won enough seats to form a government on their own, leading to renewed tensions as each had no choice but to seek a coalition deal. The Democratic Union for Integration (DUI), Macedonia’s largest ethnic Albanian party in parliament, ended its 8-year long coalition with VMRO-DPMNE and announced it would support Zaev’s SDSM instead, forcing President Gjorge Ivanov, also of the ruling VMRO-DPMNE, to grant Zaev mandate to form a government. Ivanov’s months-long refusal to do this and the political crisis itself culminated in a violent storming of the parliament by pro-VMRO-DPMNE demonstrators, and the fear caused by this violence meant Zaev was finally allowed to form a government in May.

This was Macedonia’s first leadership change in more than a decade, and Zaev made it clear even before being granted power that his mandate will be a complete break with his country’s semi-authoritarian past. Macedonia’s new prime minister aims to organise society in a different way, to improve cooperation internationally, and to strengthen his country’s democratic institutions. Zaev is also the one who exposed the underlying corruption of the system and triggered the wiretapping scandal, and his plans to change the country and ensure past abuses are investigated led VMRO-DPMNE to try to prevent his forming a government by any means necessary. Zaev has the potential, means and capacity to achieve significant reform in and for his country – but as it has been evident since before he became prime minister, he will not have an easy time doing it.

Macedonia’s strained relationship with Serbia was also brought to the centre of attention last month, with Belgrade briefly but very publicly withdrawing its embassy staff from Skopje. The official statements were unclear on the main reason behind it, with Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic saying it was due to “offensive intelligence activities” against Serbia, and that unnamed “foreign powers” were also involved. This prompted Serbian media to accuse Macedonia of tapping Serbian officials’ communications at the West’s request, while the international press seems in agreement that it was most likely a reaction to Macedonia’s alleged support for Kosovo’s bid to join UNESCO. Regardless of the actual motivation, the diplomatic row ended as quickly as it began, with Serbia returning its staff to Macedonia and the two countries announcing they have opened a dialogue on the issue. While short-lived, the row was an important signal – it highlighted the nature of the hurdles Macedonia’s government will have to overcome in its quest for progress and reform, but also made clear how crucial the leadership’s vision for the future is in the region.

Alongside external challenges, it is already clear that Zaev will also be forced to face increasingly tough internal ones. Immediately after losing their majority in the parliament and going into opposition, the VMRO-DPMNE, whose high-level officials were at the centre of the wiretapping scandal and corruption allegations that triggered the political crisis, formed ten separate parliamentary caucuses, thus ensuring that all bills, regulations and appointments will at least be stalled indefinitely. The caucuses are an opportunity for VMRO-DPMNE to use endless recesses, off-topic speeches and lengthy discussions amongst themselves as delaying tactics, since the fact that there are ten of them means that the former ruling party’s allotted time for replies to discussions is ten times longer than in normal circumstances, and that the party is now allowed ten times more recesses. The aim seems to be making sure all proposed reform is slowed down, but in reality, the main target is most likely Zaev’s ambitious plan to reform the justice system and restore the rule of law – VMRO-DPMNE knows what this means for its senior members, and it is not willing to allow that to happen.

In the less than three months that he has been in power, Zaev has furthered his country’s ambitions to join the European Union and NATO to such an extent that it suggests significant progress in the region is possible. Zaev and Borissov moving forward with the agreement shows what political will, determination and perseverance can achieve, and it is the beginning of an important conversation on how their differing views can be solved. The lessons that can be learned from this event are crucial for understanding both the region itself and how it can achieve progress. Macedonia, a country that was in political paralysis for two years, with its government unable to make any decisions and its European Union accession negotiations suspended, is showing that it is still a candidate worth taking seriously – and that, with the right leader, it can become an example worth emulating.

The Bulgaria-Macedonia friendship treaty does not mean that Sofia and Skopje no longer have any differences – it means that they acknowledge the fact that holding onto those differences is less productive than good relations between them. In a region where historical disputes continue to prevent the countries from achieving internal and international progress, this is a political move to which serious attention needs to be paid. Compromise is the way forward, and Zaev and Borissov have understood this – and it is high time that other politicians in the region follow suit.

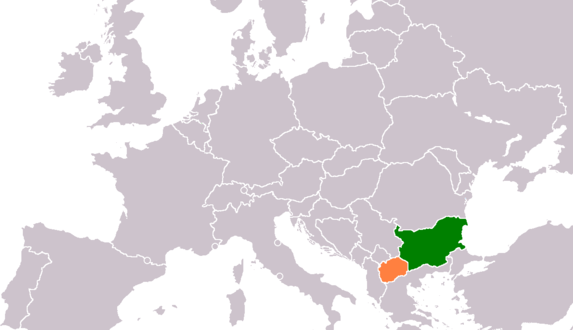

Image: Macedonia (left) and Bulgaria (right) (Source – Wikimedia/Kndimov)

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research