January 7, 2017

By Davis Florick – Junior Fellow

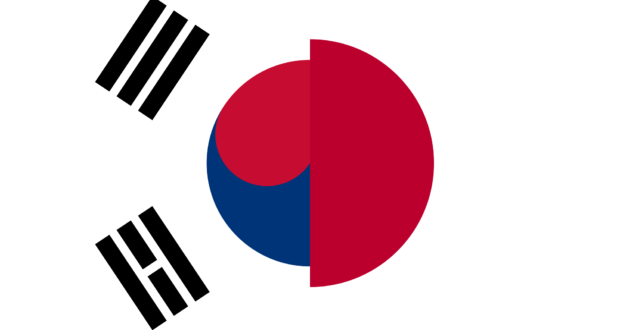

The recent agreement between Japan and South Korea to improve sharing of intelligence information marks an inflection point in bilateral relations. Stemming from a history of Japanese aggression on the peninsula, the two parties have long been reluctant partners. Yet, brought together by Pyongyang’s belligerence, Seoul and Tokyo have found common ground and an impetus for more significant cooperation. The General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA) is not the first major accord between the two states in recent memory and probably will not be the last. However, it symbolizes Japan’s and South Korea’s willingness to find an accommodation in sharing some of their most sensitive information. On one hand, Seoul offers superior human intelligence assets on the Korean Peninsula. On the other, Tokyo has the satellite collection capabilities necessary to improve early warning and increase collection opportunities against Pyongyang’s nuclear and missile programs – particularly during testing events. Moreover, as Japan and South Korea expand and strengthen bilateral collaboration, it will reduce cleavages in trilateral engagement with the US. Just as important, the GSOMIA represents another sinew, an important one, in an ever growing and tightening relationship between Seoul and Tokyo. Stronger cooperation is to the detriment of not only Pyongyang, but its patron Beijing. Collectively, the GSOMIA represents a much wider range of benefits than what might first meet the eye.

To fully appreciate the environment that has helped make this agreement possible requires a more comprehensive understanding of the threat posed by North Korea. Pyongyang’s missile test flights are now regularly reaching into Seoul’s and Tokyo’s respective air space. Given the frequency of such events, the possibility of a tragic accident has only increased. As Prime Minister Abe said during his speech at the United Nations on September 21st, “it is purely a matter of good fortune that no commercial aircraft or ships [have] suffered any damage.” While the risks of a mishap are mounting, Kim Jong-un’s belligerence is also raising the specter of a premeditated act. Amid constant threats of North Korean aggression, missile tests pose a grave risk to both Japan and South Korea. Pyongyang’s missile and nuclear programs are achieving a crucial stage in their maturity. Once it can be reasonably presumed the North has the technological prowess to mate a missile with a nuclear reentry vehicle, it will no longer be a question of capability but one of intent. At such time, how can officials in Japan or South Korea know when the next launch will be more than a test? The bellicosity and inflammatory rhetoric Kim Jong-un routinely employs could create significant potential for misunderstanding. Given the risks posed by an accident or intentional act killing Japanese or South Korean citizens, Seoul and Tokyo simply cannot afford to take a wait and see approach.

For Japan and South Korea, hedging through security investments and cooperative measures is necessary given the threat posed by the North. This particular agreement leverages the advantages of both states, thereby offering a more complete intelligence picture. Among the US and its regional partners, South Korea’s human intelligence capabilities are, likely, second to none. The obvious cultural ties enable human collection opportunities. For instance, as the primary destination for North Korean defectors, Seoul can gather considerable information from well-placed individuals. Likewise, its relationship with defector support networks along Beijing’s border with Pyongyang fosters a unique ability to peer into the Hermit Kingdom. These assets are simply unmatched by Japan or the US. Conversely, Tokyo continuously monitors Pyongyang’s activities. Japan’s ability to collect intelligence via satellites is key to better understanding the technical aspects of Kim Jong-un’s missile and nuclear programs. Combining knowledge of human and technical factors will permit Seoul and Tokyo to better anticipate Pyongyang’s future actions. More importantly, having a better idea of when Kim Jong-un might conduct another inflammatory act might aid Japan and South Korea in preparing and planning response options. Additionally, improving intelligence capabilities will reduce the risks of misperception and misunderstanding. Being able to minimize uncertainty is the best means to reduce the chances of miscalculation, particularly as the North crosses the capability threshold.

Beyond the immediate utility of bilateral cooperation, there are significant trilateral benefits, involving the US, that substantially magnify the utility of this agreement. Since the start of the Cold War, Washington has relied on a multilateral approach to engagement in Europe, yet was forced to depend on two bilateral partnerships in Northeast Asia. Tensions between Seoul and Tokyo not only served as an impediment to bilateral cooperation, but significantly hindered trilateral dialogue. Rather than linking all three states together, communication would occur between Japan and the US, as well as South Korea and the US. With Washington bridging Seoul and Tokyo, there were persistent questions about how this might hinder collaboration and interconnectivity during a conflict. The GSOMIA symbolizes a noteworthy milestone in the transformation of these dynamics. This agreement will assist all three states in communicating more freely. Furthermore, as the benefits become more apparent – with Seoul and Tokyo becoming able to improve their awareness of activities taking place in the Hermit Kingdom – the GSOMIA could lead to a broader range of cooperative measures. Once Japan and South Korea improve their communication, it will amplify the already high degree of cooperation between these two states and the US as the community shifts from multiple bilateral relationships to a more streamlined trilateral mechanism.

From the perspective of Beijing and Pyongyang, this agreement is viewed as complicating matters in Northeast Asia. At one time it would have been fair to question whether Japan would actively support South Korea in a conflict on the Korean Peninsula if Tokyo were not attacked. Likewise, questions could be raised over South Korea’s willingness to support Japan in a similar scenario involving China. Particularly after Beijing established diplomatic relations with Seoul, there were doubts over South Korea’s willingness to assist Japan. While questions regarding the strength of Seoul and Tokyo’s bilateral relationship may still exist, these concerns are diminishing. Against Beijing’s wishes, the two states finalized the GSOMIA. For South Korea in particular this is the latest in a series of decisions that have rankled Zhongnanhai – perhaps most notably Seoul’s acceptance of a Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) battery from Washington. Taken together, it is increasingly difficult for North Korean apologists in China to argue that defending Pyongyang is working. Rather, it is only driving Seoul closer to Tokyo at a time when South Korea could be part of China’s answer to revitalizing its northeastern economy.

One would be remiss to not make some mention of the ongoing political turmoil in South Korea. With Park Geun-hye’s impeachment on December 9th, political uncertainty in Seoul will only mount. The Constitutional Court is now determining whether to remove her permanently – a decision may take as long as 180 days. In the meantime, South Korean defense officials have expressed the need to move forward on THAAD, the GSOMIA, and other mechanisms designed to improve the state’s defensive posture. While the defense community moves forward, Korean political parties were already preparing for a presidential election in late 2017. Although the timetable may now be accelerated, the basic foreign policy divide – particularly over North Korea – is clear. While President Park’s Saenuri Party has a vulnerable economic platform, the liberal opposition, most notably the Minjoo Party, appears to have an unfathomable foreign policy posture. The recent accusation by sitting members of parliament that President Park is “on the warpath” and calls for the dismissal of the Defense Minister for signing the GSOMIA, do not align with a rational platform. Considering that in polling done during 2016 ~65% of South Koreans supported their state’s nuclearization and a plurality, ~43% regarded North Korea as an enemy, liberal opposition’s chances of a victory at the ballot box could be severely compromised. Although Ms. Park might have jeopardized the Saenuri’s chances of matching their success in 2012, the South Korean people appear to favor her foreign policy.

Seoul’s domestic uncertainty aside, mounting cooperation between Japan and South Korea is best-symbolized by the GSOMIA. This agreement will enable intelligence exchanges for the two parties on matters pertaining to Pyongyang. By leveraging Seoul’s natural advantages in human intelligence and Tokyo’s strengths in satellite capabilities, both states will gain a far better understanding of activities taking place in North Korea. These improvements will help reduce Kim Jong-un’s ability to surprise his neighbors, therefore extending decision times for senior officials in Japan and South Korea. Beyond the readily apparent advantages for both parties, upgrading communication on a bilateral basis will reduce impediments to trilateral cooperation with the US. Therefore, not only does the GSOMIA serve to enhance Japanese and South Korean security, it serves as a political tool in demonstrating cohesion and resolve – a message clearly received by both China and North Korea. Despite domestic opposition in Seoul, this agreement is a powerful mechanism in changing dynamics in Northeast Asia.

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research

Human Security Centre Human Rights and International Security Research